BMW Group — LeSS Huge at Autonomous Driving

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge the BMW Group for the opportunity to learn, grow, and analyze a fascinating LeSS Huge case in a highly competitive and challenging environment. We also thank all LeSS Trainers and Coaches who were present at the BMW Group during this journey.

We sincerely thank our mentors Mark Bregenzer and Viktor Grgic, who accompanied our development from the early days. And special thanks to Viktor Grgic for re-viewing and re-writing this experience report and always finding time to talk with us.

Craig Larman, thank you for your endless patience with us when (again) re-writing the case study and coaching us. Bas Vodde, thank you for your support, for continuously answering our (often nagging) questions, and supporting us on our way.

A big thank you to our colleagues and friends for their support!

And most strongly, we thank our families for their endless mental support on this journey.

It was and continues to be a deep and transformational learning experience for us.

Introduction

The BMW Group decided to go through a significant change to deliver the highest customer value, learn faster than competitors, and create an easily adaptable organization to ensure its first two goals. It is still in the middle of its journey.

This report is an in-depth examination of BMW Group’s LeSS adoption in the autonomous driving department. It covers mid-2016 until October 2019, and the LeSS adoption is still ongoing.

The authors are Konstantin Ribel and Michael Mai. The real names of the people are left out for legal reasons.

The report is structured with multiple views (perspectives) on to the change:

- Timeline View

- Technology View

Start with any view you like!

Terms: LeSS and Scrum terms are capitalized, such as: Sprint, Product Backlog, Team. Note: Team is the role in LeSS whereas team is the general concept of a team.

Background

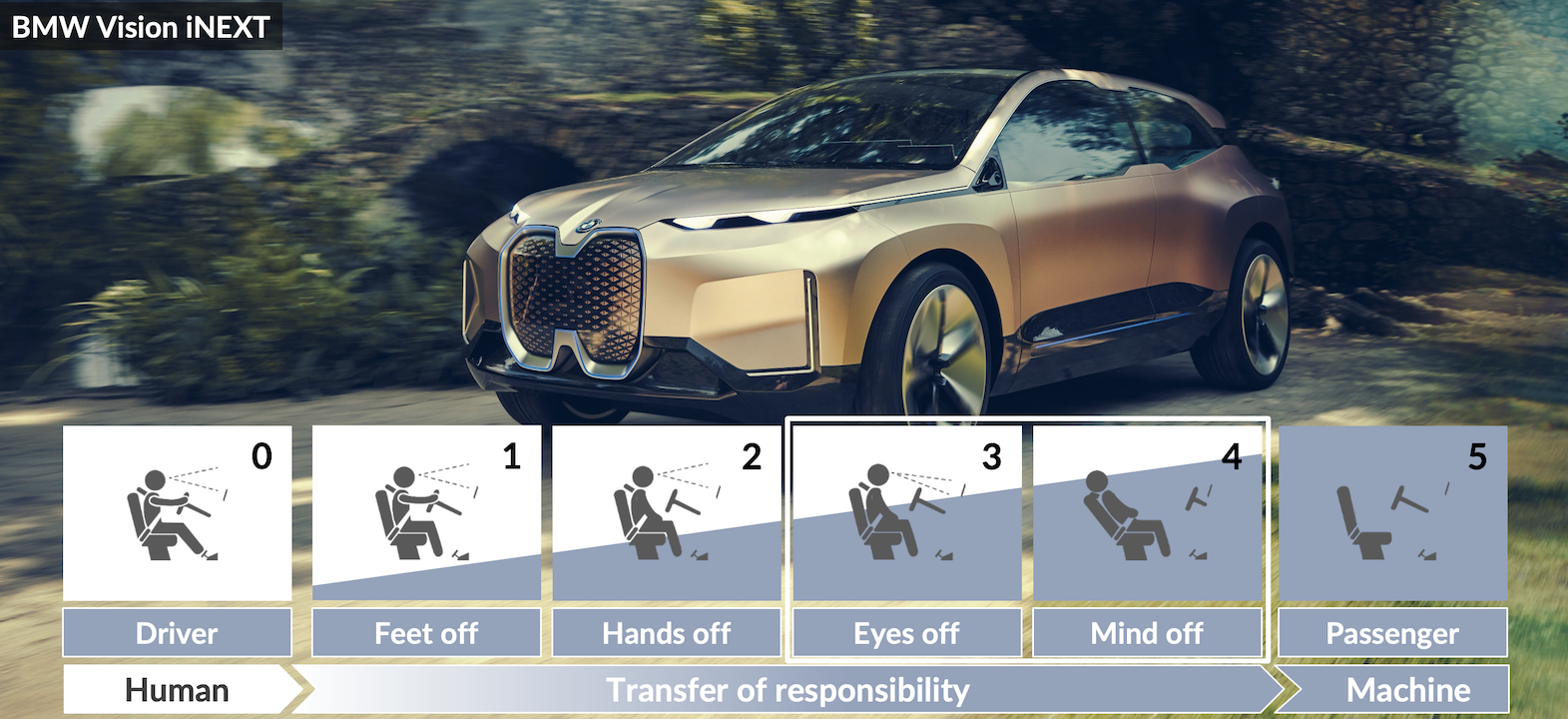

On BMW Group’s journey as an automobile designer and manufacturer, its main focus is to provide more safety, comfort, flexibility, and quality through Level 3 autonomous driving (AD) (see Figure 1). There are many challenges to overcome on the way to AD, and perhaps the most significant is its inherent complexity.

To create something as complex and software intensive as AD, BMW Group has to shift from a 100-year-old company of mechanical engineering and manufacturing skill to a software company and treat AD as a complex software research and development (R&D) initiative. It sounds like a revolution and a paradigm shift. It is!

As an early step, BMW Group gathered all the people to be involved in AD and co-located them at one site—the BMW Autonomous Driving Campus. Why? Because they anticipated that succeeding in such a hard problem—combined with a paradigm shift—would be even more difficult if multiple sites were involved.

Then the BMW Group did what no one expected: they deeply changed their traditional organizational design towards one optimized for making learning and adaptation easier in a large group. And for that they took inspiration from LeSS.

So far, the journey has been full of failures and pain, but also full of positive effects such as closer collaboration between departments, leading to less inventory and handoff between groups of people. A higher focus on self-managing teams and frequent retrospectives led to teams designing and owning their processes. Higher emphasis on technical excellence led to better software design, cleaner code, and a more adaptive technical stack.

Timeline View

Three pronouns I, we and they provide different perspectives in the timeline view. It starts with the author’s personal experience—I and we form. Then it transitions to the they form, presenting an external view on many situations, providing a more impartial observation followed by a root-causes analysis and suggested measures.

How it all began

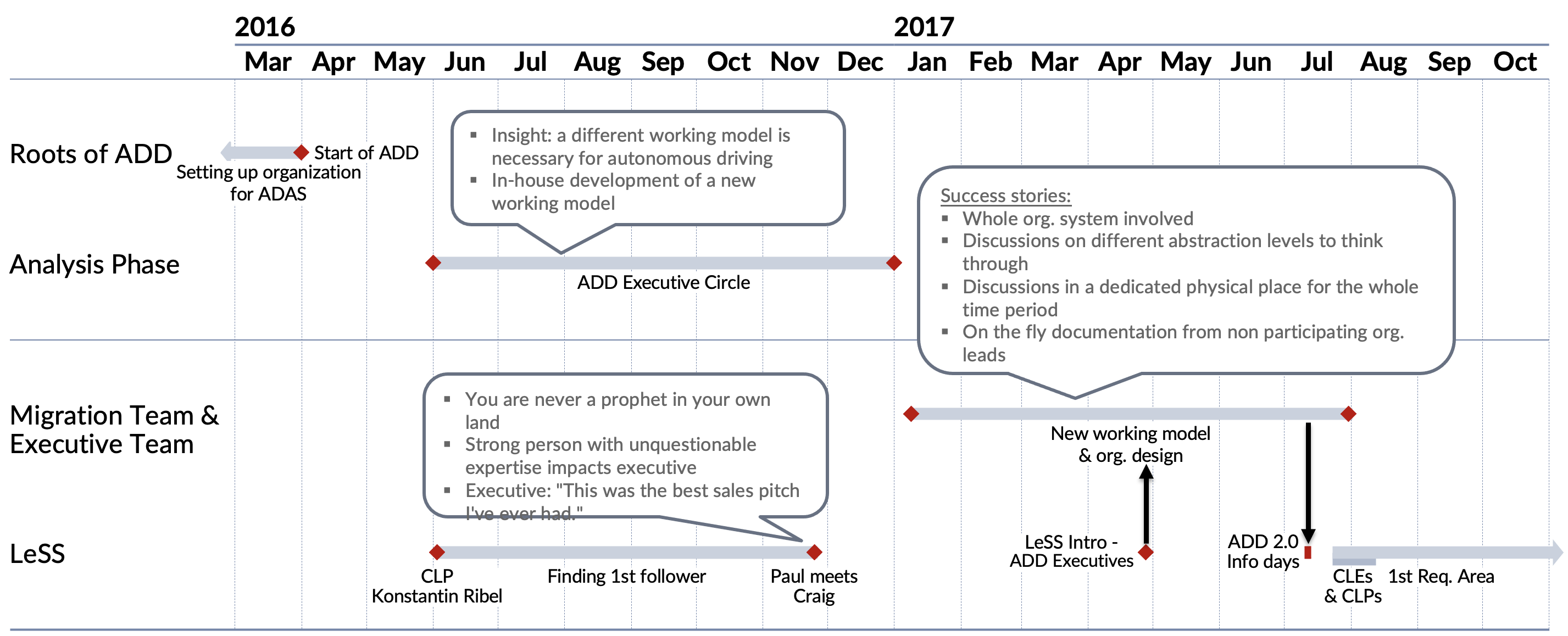

After a successful launch of a new car in 2015, I (Konstantin Ribel) was looking for a new challenge. The Highly Autonomous Driving project had just commenced at that time. I joined the project at the beginning of 2016.

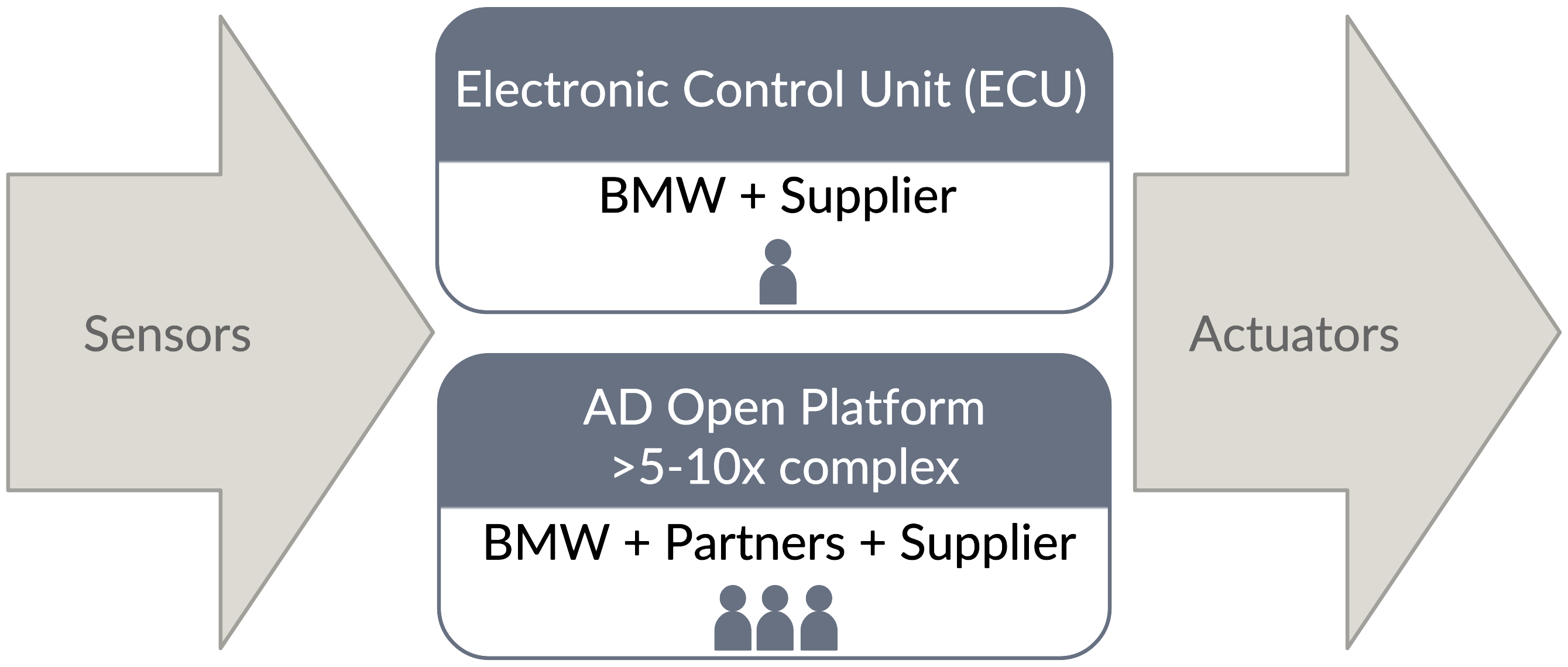

One of my main tasks was to create an efficient working model for developing our complex AD open platform, which involved BMW Group, cooperation partners, and vendors. For a standard complexity Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems (ADAS) Electronic Control Unit (ECU), we usually have a team interfacing with one vendor to develop it. For the AD open platform and its multi-processor hardware design, we estimated 5-10 times greater complexity, several vendors, and cooperation partners. We further discovered that if we scaled this up linearly, we would probably need 10-15 times more people solely for the vendors’ project management interface (see Figure 2). I realized that something had to change to improve it.

While looking for a solution, I read several Scrum and agile development books. Then I was recommended to talk to Mark Bregenzer—an agile coach and LeSS trainer. I met Mark and explained our situation. His answer was, “You need way fewer people than you can imagine. You need to change the organizational structure.” After this meeting, Mark recommended that I participate in a Certified LeSS Practitioner (CLP) course with Craig Larman.

I participated in the CLP course in June 2016 in Berlin. On the second day of the CLP course, I realized that all of my roles at work manifested the lean wastes—”moments or actions that do not add value but consume resources.” [1, p. 58]. Who wants their work to be a waste? I was devastated. After the course, I realized that I wanted to reduce the lean waste in the environment I worked in, and I was sure that my colleagues would want that too.

When I returned to the office, I tried to convince my line manager’s superior (“Paul”) that we should adopt LeSS in our department. Initially, this was anything but successful. We had a dispute about how this was never going to work in our environment. It was a very disappointing experience for me. However, I recalled Craig frequently repeating the following phrase during the CLP course: “Think and act like a politician [when introducing change], not like an engineer.” I realized that I needed to act differently and stopped pushing this topic.

Let’s take a look at this story from a different perspective.

Between September 2015 and March 2016, an effort was made to set up an organizational unit for future ADAS systems, including AD. Еxecutives of several departments worked together to accomplish this task. On April 1st, 2016, Several departments from different organizational units merged to form the new department for autonomous driving and ADAS (ADD—autonomous driving department).

A short time after ADD’s start, there was an insight that within the existing setup, there was, among other issues, a high amount of coordination overhead and hand-off between departments, groups, and roles that were slowing us down. It was a weak starting position for a complex product with many uncertainties and unknowns, such as AD. To improve this situation, the ADD executive board worked between June and December 2016 on a new working model and organizational setup.

During this time, Craig Larman was on-site and taught our developers legacy-code TDD. I invited Paul to meet Craig at the end of November 2016. He took the offer. Craig and Paul spoke for about 20 minutes. Those who have met Craig know how honest and precise he can be. During their conversation, I did not know whether it was a good idea to let them talk to each other. Among other topics, Craig introduced Paul to Larman’s Laws of Organizational Behavior and shared with him the English proverb “you are never a prophet in your own land.” The further the conversation went, the more uncertain I became about its result. When Paul and I left the room, Paul said: “This was the best sales pitch I’ve ever experienced.” It was a success! Paul became the first like-minded person on the executive level. The momentum for the change began to rise.

A so-called migration team, which I was part of, was founded in January 2017. To represent the whole organizational system, this team consisted of managers and employees from different levels. It allowed us to discuss ideas through different abstraction levels. We continued to work on the working model that the ADD executive group had come up with the year before. We discussed different use cases, everyday situations, and how they would look if we adopted this working model. We were continuously working on the proposal to improve the situation we had.

Meanwhile, Paul convinced the ADD executives to have a 4-day workshop with Craig Larman on systems thinking and organizational design for large-scale agile development, also known as the Certified LeSS Executive course. To ensure full executive representation and due to their availability, this event took place a few months later. To get the ball rolling before then, in April 2017 I organized a one-day introduction workshop with Mark Bregenzer.

The content, presented by Mark, inspired participants. It was evident that we needed to move in this direction. This initial workshop created the next significant momentum shift.

At this point, the ADD executives were certain that to really change the behavior and the organization’s working model, they needed to change the organizational structure.

Summary of Beginning Lessons

- Think and act like a politician, not like an engineer

- Gain allies across different hierarchy levels and align your shared goal—real change is only possible as a group, both top-down and bottom-up. LeSS guide: Three Adoption Principles [3, p. 55-59].

- Educate all senior executives and directors, especially those with true decision-making powers [3, p. 57].

- “You’re never a prophet in your own land.” Engage an external expert, experienced in large-scale organizational design for agile development. This expert—a great trainer and a great coach—will have a focus on the Why and will make a positive difference in your LeSS adoption. More on this topic in the section “Teach why” in the book Large-Scale Scrum [3, p. 60].

- (LeSS guide: Getting Started)

Preparation Phase

The Way to the Insight that Organizational Change is Necessary

LeSS adoption involves big organizations and many minds with deeply rooted assumptions about how organizations should work. Successful adoption requires challenging these assumptions and simplifying the organizational structure, with all the explosive politics and “loss of face” that working across a big group entails. Adoption needs everyone to improve towards a shared goal. [3, p. 54]

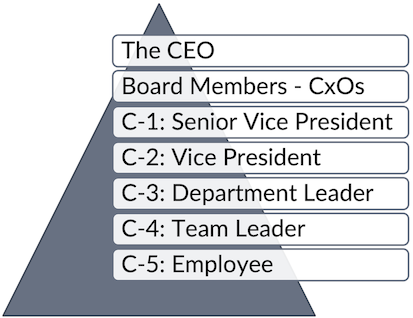

Our starting position was a common hierarchy (see Figure 6).

ADD inherited from its origin departments more than 15 different roles with defined interfaces, clearly describing where someone’s work starts and ends. With this setup, we successfully delivered many great cars to our customers. However, it is fertile ground for the lean-thinking wastes, such as hand-off, coordination overhead, and many others. Since waste inhibits adaptivity in complex product development, especially large-scale, we had a compelling motivation to change.

This phase started in May 2017, directly after the one-day introduction workshop with Mark Bregenzer. At this point, the answers to the following questions were open:

- How do we want to work?

- Which working model are we going to adopt?

- If it will be Scrum-based, which scaling framework is it going to be?

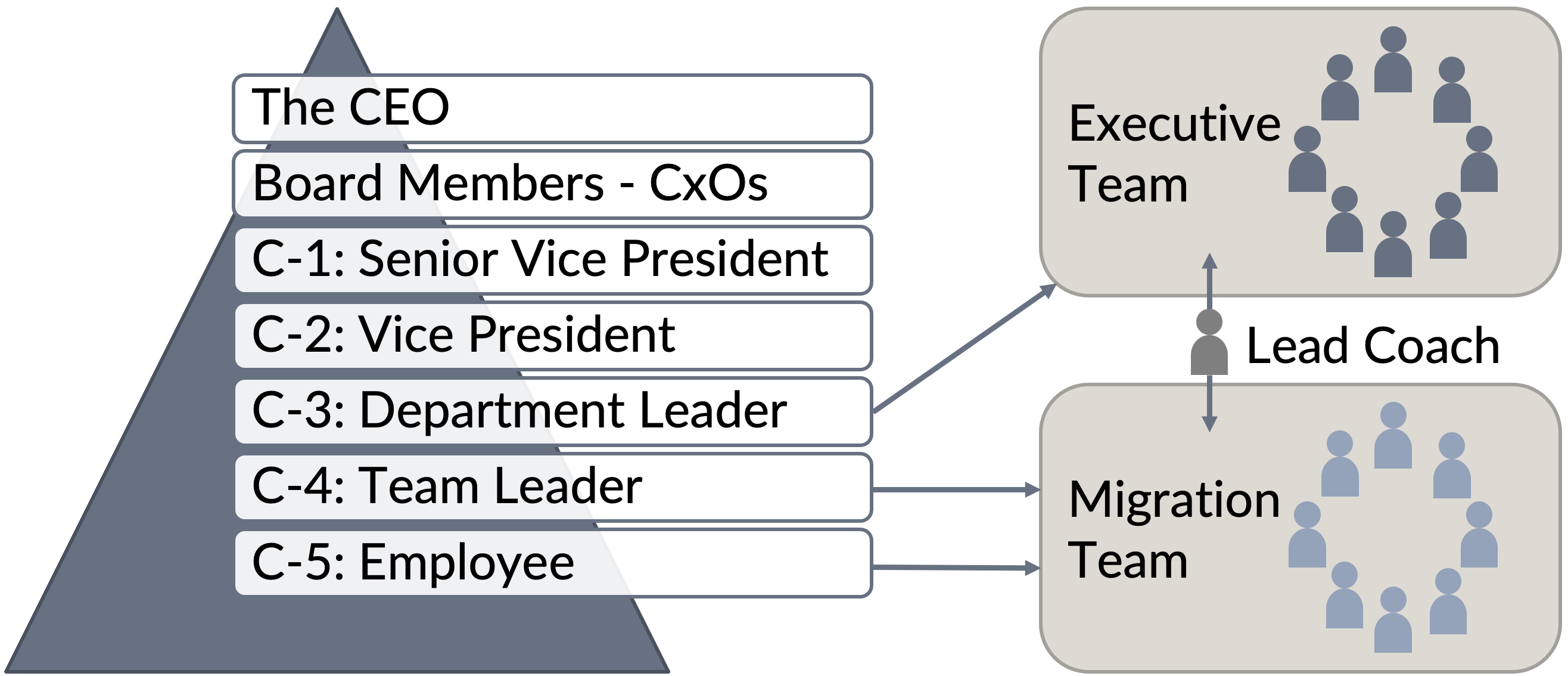

To answer these questions, we needed to include the whole organizational system, including all relevant stakeholders from the rest of the BMW Group. We set up two teams. The existing migration team was too large, and therefore we shrunk it. The second was the executive team with a maximum of 10 members, as shown in Figure 7.

With this setup, we involved people who were highly engaged in product development and managers with far-reaching decision making powers. It allowed us to verify ideas and make decisions quickly.

Further, there was Mark Bregenzer, who challenged our assumptions about organizational structures and coached us on the Why. We worked full-time on this topic.

Both teams and Mark worked in diverge-merge cycles. The migration team and executive team representatives explored answers to the question: How do we want to work? In a multi-team setup, both teams debated the rationale behind possible solutions. The representatives worked out organizational designs which hypothetically would support the proposed solutions. Then, the whole ADD board (C-1 and C-2 level) and the executive team reviewed both teams’ proposals, meaning the answers to the “How do we want to work?” question and the supporting organizational design.

Both teams worked closely together, allowing fast feedback and short iteration times for their ideas.

A few weeks later, after both teams gained many insights, the organizational design’s optimization goal became apparent. First, no one in the world knew exactly how to make an autonomous-driving car production-ready. Therefore, learning what and how to do it becomes vital. Consequently, it requires an organization to become a learning organization.

Second, faster feedback loops improve learning. Since no one had yet built an (SAE Level 3 and higher) autonomously driving car, learning from reality, adapting the Product Backlog, and working on the highest-priority items was necessary for any hope of succeeding. That meant short cycle time, early integration, and prototype cars driving on public roads. In other words, using feedback loops to learn and then to decide what to work on next. Consequently, the ability to always work on the newly discovered most critical items requires an adaptive organization.

The above led to the following optimization goals:

- Ability to learn faster than competitors

- Based on that learning, ability to work on and deliver the highest customer value

- Easily adaptable organization to ensure (1) and (2)

It was necessary to remove waste to achieve the optimization goals. First, coordination overhead needed reduction. For example, identifying the right people with experience and expertise for focused discussions, and particularly excluding middle management, to avoid individual tactical career games that disturb these discussions and usually increase the overhead.

Second, hand-off waste, especially between component teams, single-function silos, and individual responsibilities, needed removal. The guiding goal was: increase shared responsibility across functional groups.

We thoroughly analyzed whether all of it was achievable with LeSS in our domain. For this analysis, we invited people who were not part of the migration and executive teams, who had different roles and use cases. We let those people challenge the LeSS working model and thoroughly discussed their use cases, such as defects handling and coming to a driving approval for public roads in the context of safety-critical software and shared common code. The discussions focused on how we can achieve the use case results with LeSS.

We were looking for use cases where it was not possible. We didn’t find any.

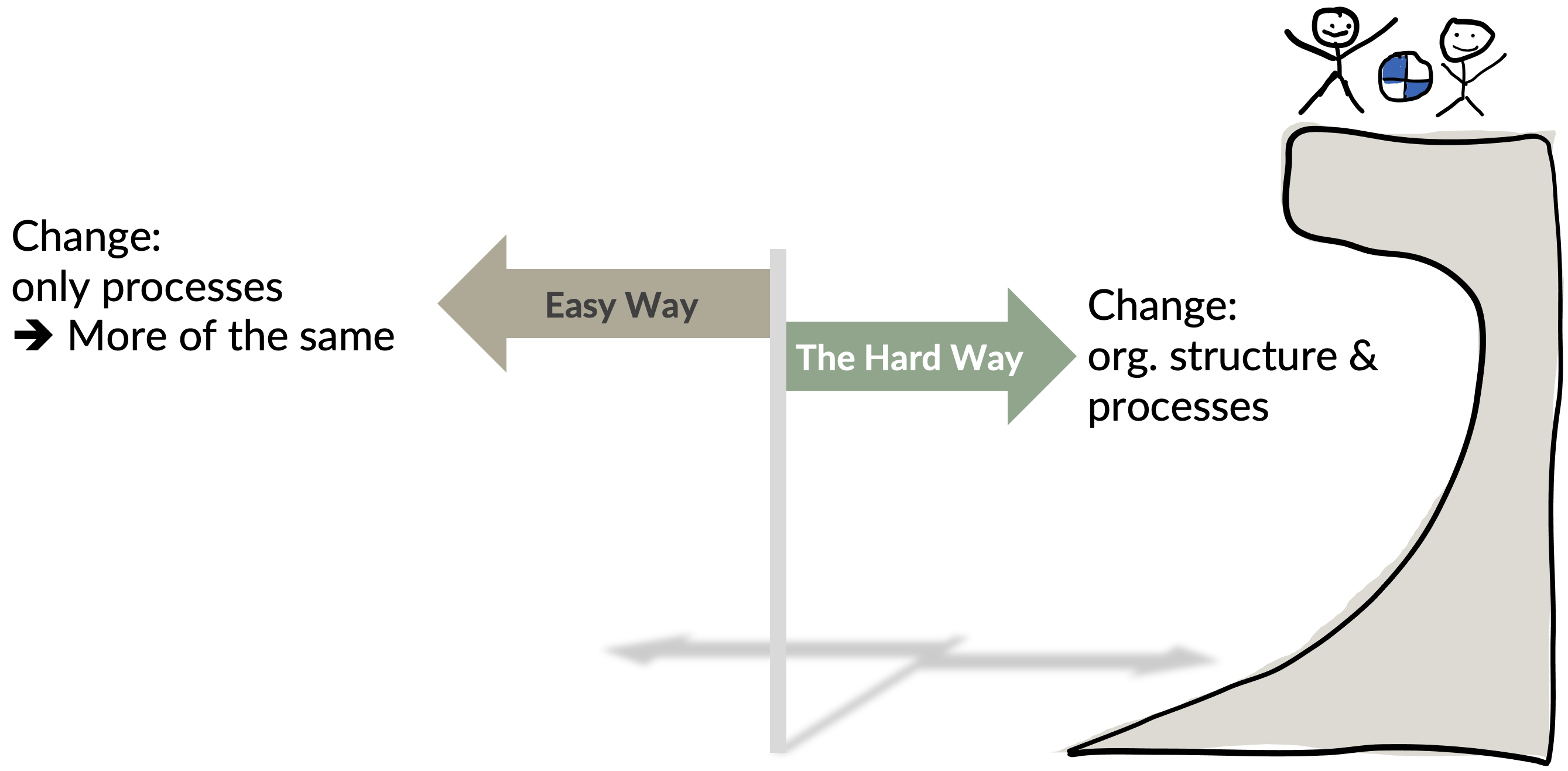

The executive team had in addition to LeSS other proposals on how to achieve the result. Only one required any changes in the organizational structure—the hard way. The others just needed changes in practices—the easy way. The executives already learned that just changing the practices without restructuring the organization design does not change much of anything. Some executives called those attempts “more of the same” with different labels.

In contrast, LeSS required deep changes in the organizational structure—the harder way, but more likely to support the goals. The decision was to adopt LeSS (June 2017).

Product Definition

AD is driven by customer demands and legal requirements. New technologies and seamless connectivity are paving the way. The technological challenges are enormous. Building up data centers, training AI algorithms, virtual test and validation, developing new sensors from scratch, bringing non-automotive high-performance hardware to the car and qualifying it for automotive use, and complex system architecture just to name a few.

What is the Product for This LeSS Adoption?

The product definition determines the scope of your Product Backlog and who makes a good Product Owner. When adopting LeSS, it determines the amount of organizational change you can expect and who needs to be involved. [3, p. 157]

A customer would most probably describe AD as a mobility service spanning a range from a smartphone app, over mobile networks, cars, sensors, algorithms, actuators, tires to road infrastructure. The list is long, and this is just a technical perspective. From a legal perspective, there are insurance questions to deal with, road clearances, law changes, etc. Many parties need to be involved, to live up to this product definition. In addition to BMW Group, there are governments in each country, insurance companies, vendors, service providers, and many others. The customer perspective might be correct, and simultaneously, it is unfeasible to start a LeSS adoption at this scale.

There are forces that restrained the product definition:

- Organizational boundaries for the LeSS adoption;

- The parties which can be involved

Both forces naturally restrained the product definition to a car with an autonomous-driving feature where the BMW Group was the main party. This product definition required collaboration with other departments within the BMW Group and vendors who did not adopt LeSS.

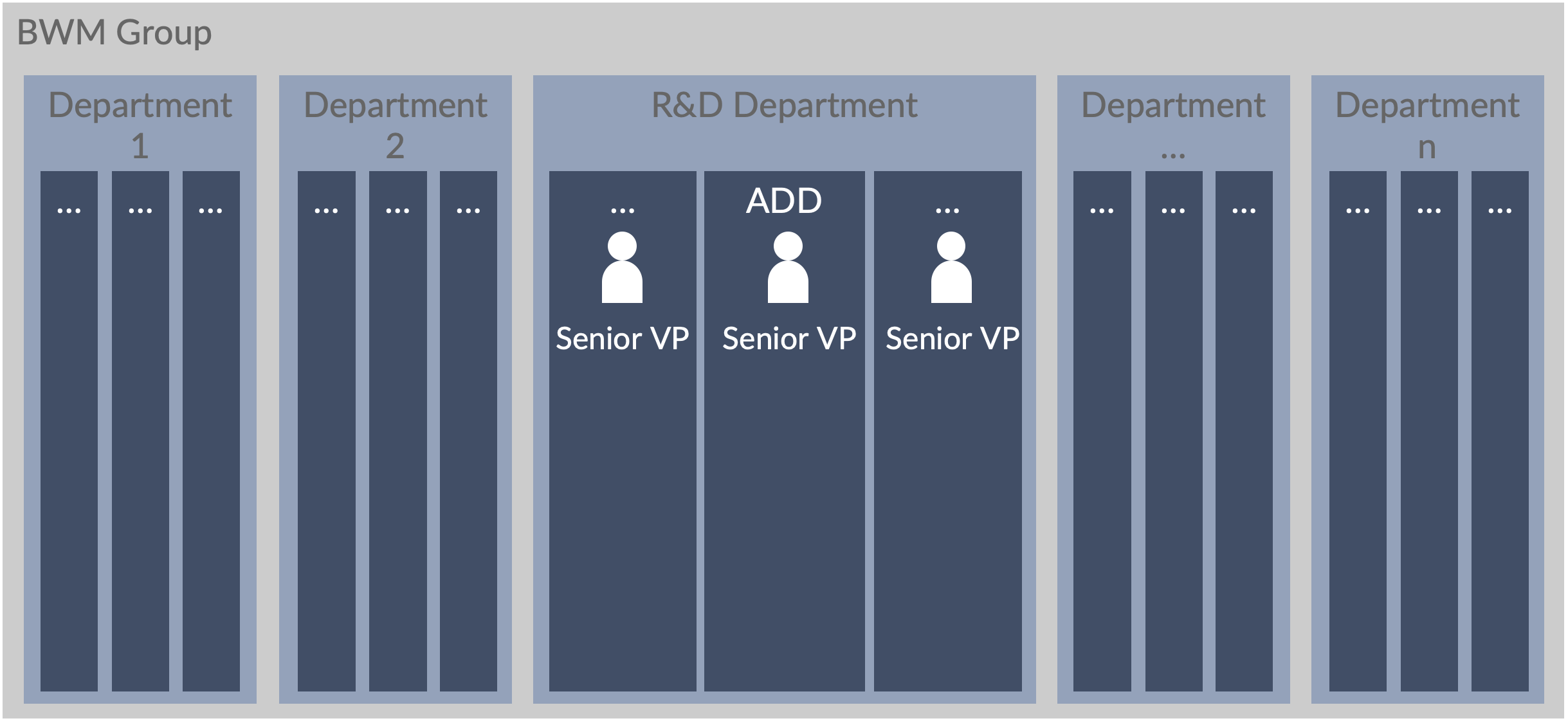

Figure 11 provides an overview of the organizational structures within the BMW Group. Each department within R&D had its dedicated senior VP. The ADD senior VP sponsored this LeSS adoption, which naturally limited it to the organizational boundaries of ADD. Consequently, existing interfaces and working models to other departments and parties outside the ADD needed to remain intact.

Most product development is organized as projects—every new product release is a new project. Organizations manage development by managing projects … [1, p. 236]

This quote describes perfectly the situation at BMW Group. Let’s take ACC (Active Cruise Control) as an example. The BMW Group released its first version of ACC in 2000. With each further release, ACC gained new improvements and could handle more and more traffic situations. The product enhancements over multiple releases make it a product development case.

A term needs definition before continuation.

Start of Production (SoP): A major milestone. It involves an updated or new car model whose production will start after this release. Further, the technology stack (hardware and software) is updated.

Despite the long-lived products, the SoPs were organized as projects.

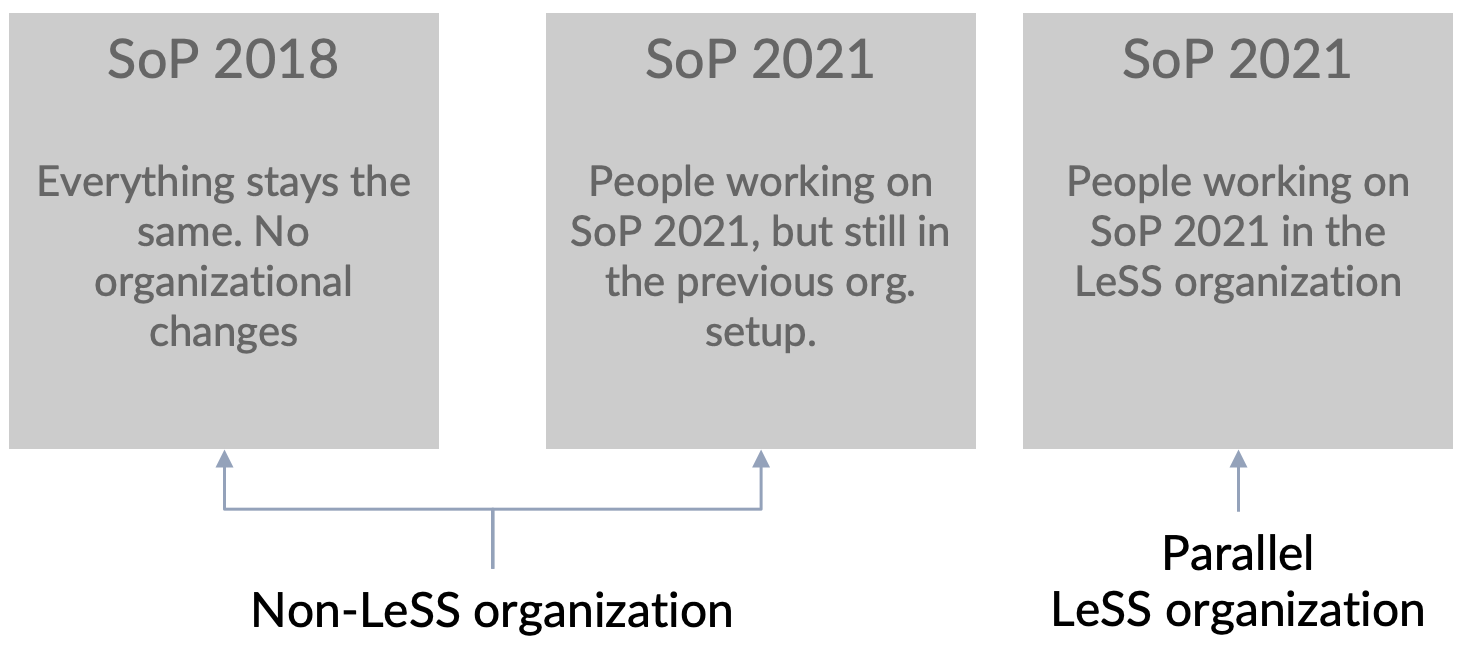

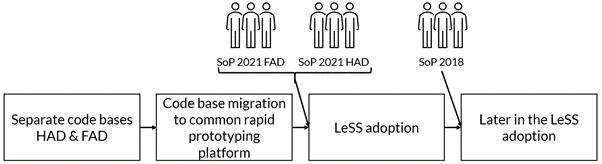

ADD had two big projects, SoP 2018 and SoP 2021. To ensure stable delivery for SoP 2018, involved people were excluded from the LeSS adoption. They could join the LeSS organization after the release. Therefore, their organizational setup remained mostly unchanged.

This decision also excluded the SoP 2018 product scope from the possible product definition.

As a consequence, the product definition for the LeSS adoption became the release scope of SoP 2021, excluding the SoP 2018. Mainly ADAS functionality on SAE Level 2 and AD for SAE Level 3. It involved the development of sensors, computing hardware, and software. It also required collaborating with departments and vendors outside ADD, who did not adopt LeSS.

Further, AD should be offered as a separate Autonomous Driving Platform (ADP) to other automobile OEMs.

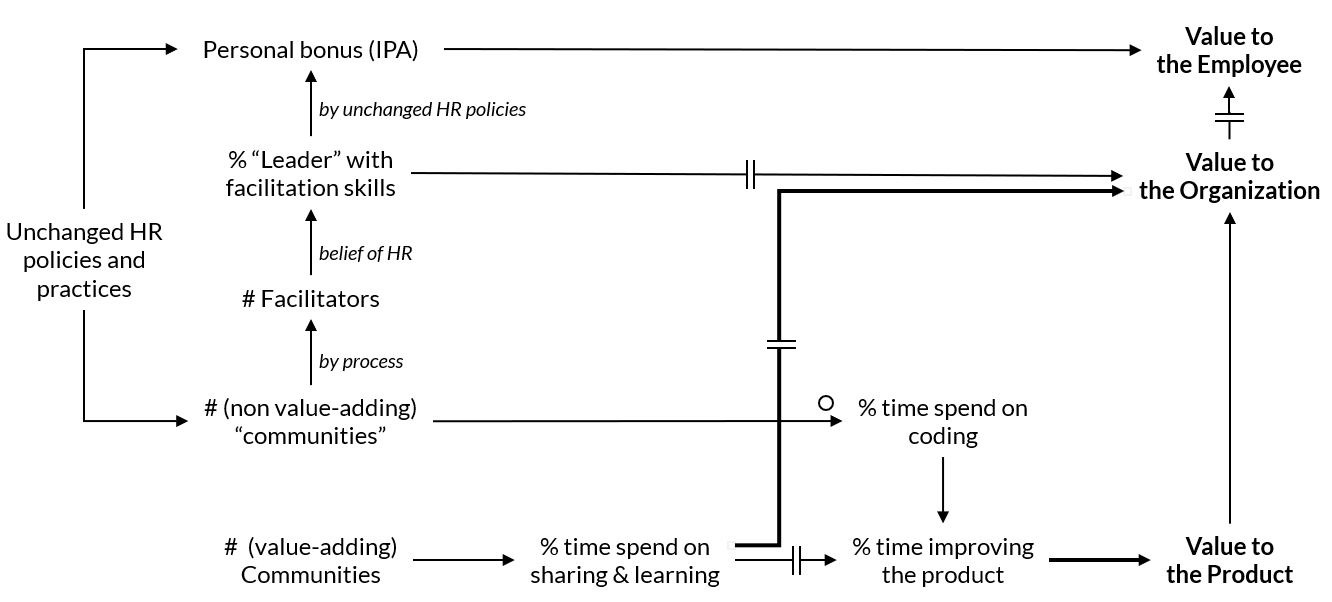

Establish the Complete LeSS Structure At The Start

LeSS requires small, end-to-end, self-managed teams coordinating towards a common goal while sharing the responsibility to achieve it. Our starting position was far away from the intended one (see chapter The Way to the Insight that Org. Change is necessary). Further, our mindset, which formed over decades, supported single-function groups, heroism, component teams, and only one career path that required a switch from technical to a management career. We had concerns that without changing the rewards system, people would not change. Therefore, we faced the question, “If, when people cooperate they are individually worse off, why would they cooperate?” [6].

It led us to the insight that we needed to create an organizational design which would foster a culture “… in which it becomes individually useful for people to cooperate” [6]. You can find more on this topic in the Culture Follows Structure guide.

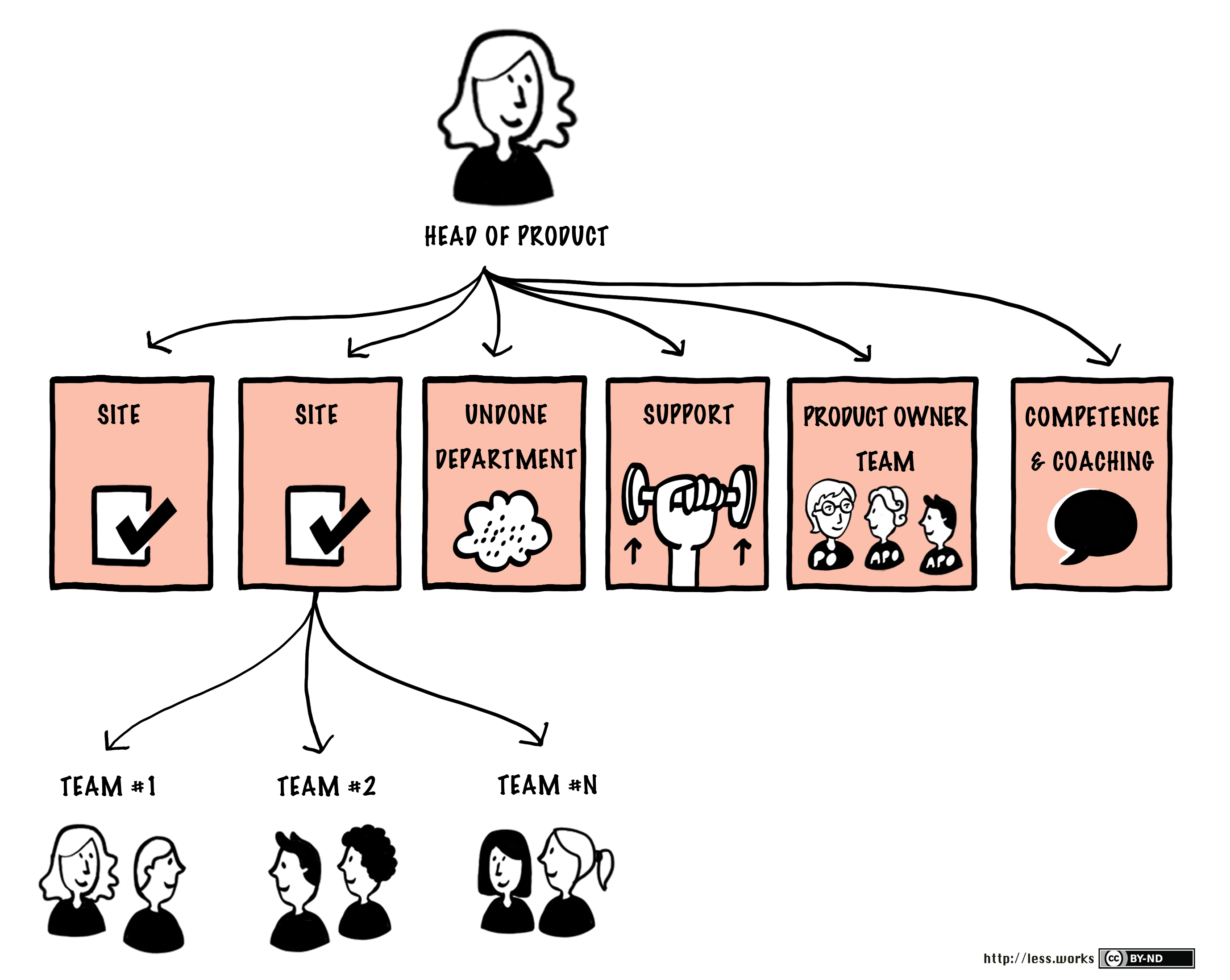

The LeSS Rule “… establish the complete LeSS structure ’at the start’” was followed. We designed our new organizational structure guided by the typical LeSS Huge organizational chart (see Figure 12).

Both the migration and executive teams played an important role in inspecting previous organizational structure, and applying systems thinking to change the organization towards the “learning and adaptiveness” goal.

We had concerns that any cross-functional and team-based organization would, over time, inevitably revert to the old paradigm of single-function groups. The deeply ingrained BMW culture and structure, which was very different from the desired one, was (and remains) a strong force that reaffirmed our concerns. We decided to resolve this by making significant and immediate changes in the structure (see Figure 13). We adopted this to counter the tendency to fall back into old habits. The following paragraphs explain each part of the structure.

Step 1 - Set up a Development Department (Feature Teams and a Management Team)

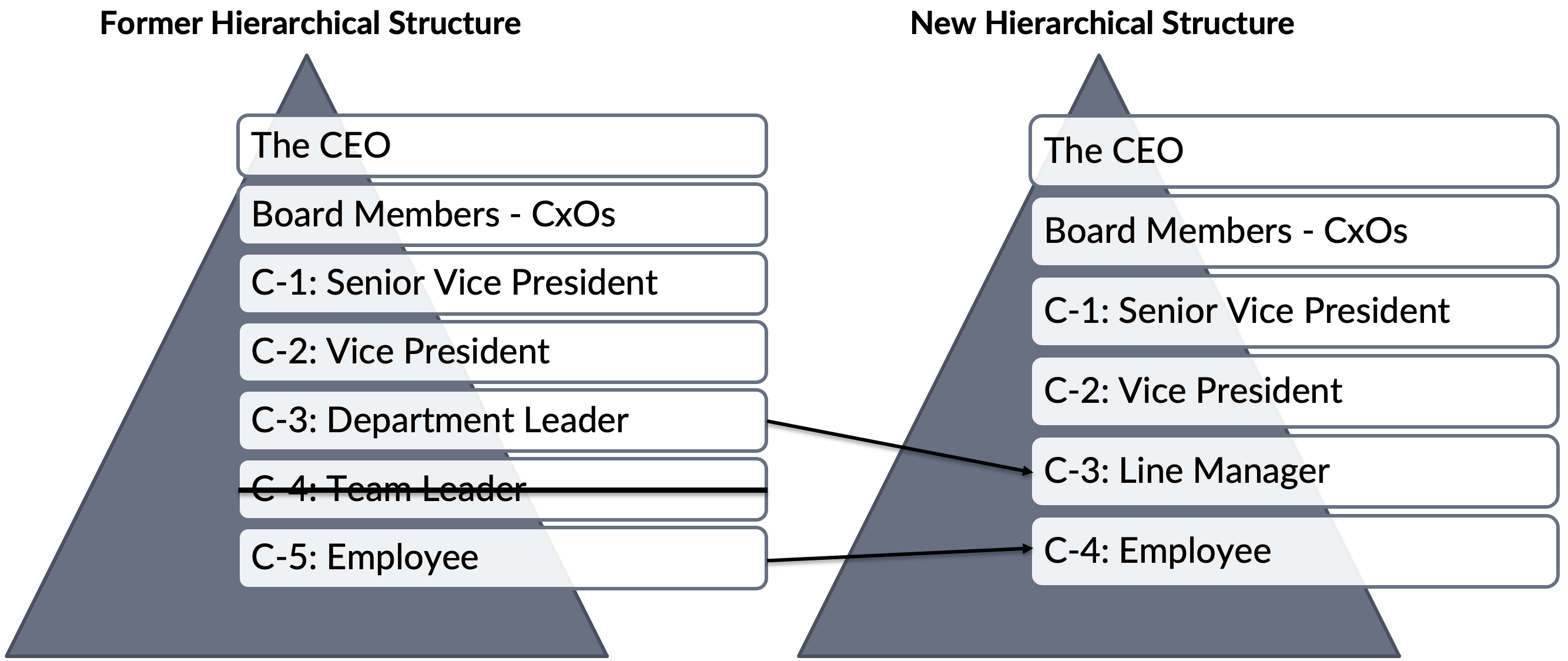

This step starts by removing one full hierarchy level, the role of team leaders (C-4 level, see Figure 14), which leads to a remaining group of line managers each being disciplinarily responsible for approximately 60 product developers. Which, in turn, creates several opportunities to form cross-functional and cross-component teams.

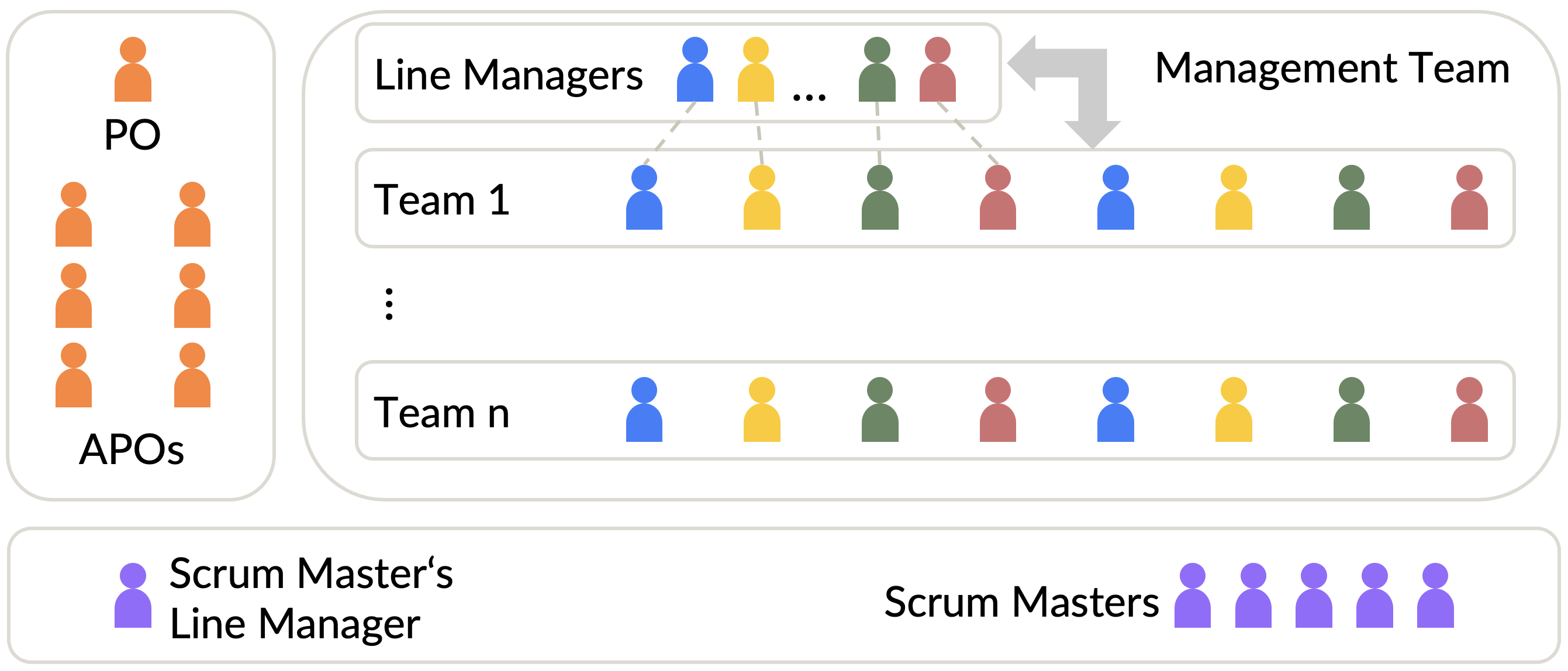

How to set up connections of feature team members with line managers (which was required at the BMW Group)? We considered two options.

Option 1: Feature Team Members Having the Same Line Manager

One option was to arrange the eight teams (one Requirement Area) per each line manager.

Advantages? We couldn’t think of any except variations of local optimizations.

Disadvantages? The concept of Requirement Areas demands flexibility. They must be easily set up and dissolved. It must be cheap to reassign a team from one Requirement Area to another. However, this option brings a degree of organizational stiffness with it. If a Requirement Area is an organizational unit, reporting to one line manager, then it would require formal organizational changes to, for example, reassign a team from one Requirement Area to another, or dissolve the Requirement Area.

Other disadvantages when considering this option over time and scale:

When coming closer to a release date, delivery pressure would increase. Then, old behavioral patterns could revive. The managers could be made “responsible” for their teams’ performance, leading to command-and-control behavior. In this situation, managers would be likely to focus on the teams rather than on the system for the teams. This, in turn, would lead to managers interfering with teams and their Scrum Master’s area of concern.

Further, in the previous setup, the future line managers were single-function group managers (e.g., manager of the architecture group) on C-3 level, having team leaders on C-4 level reporting to them. Therefore, they were likely to be biased towards (1) their original single-function activity and (2) building up an informal layer of team leaders (even though the official position of team leaders was removed). Why would they do that, and why is this a problem?

First, note that promotions would remain manager-driven. And climbing up the career ladder at the BMW Group requires at some point to demonstrate management skills. Therefore, it’s possible that employees attending more to the specialty of the manager (e.g. architecture) might gain more favor, and even be informally supported by the manager to take a more active “leading” role in their team. This could create an informal hierarchy within an ostensibly self-managing team and “…destroy the team’s shared responsibility and cohesion.” [3, p. 63]

Option 2: Feature Team Members Having Different Line Managers

The second option’s main goal was a high degree of flexibility in changing Requirement Areas as needed.

We considered teams with developers having different line managers (see Figure 13). With this setup, each line manager would have around 60 product developers distributed over many teams.

Advantages? A high degree of flexibility to easily change Requirement Areas without changing formal organizational structures.

Further, this setup would expectedly force line managers to optimize globally. How? This option would equally authorize line managers towards the teams. It would likely reduce the effect of managers using their authority towards a specific “my team” to optimize locally. It would create the context that the line managers act as an aligned management team towards the teams—a positive application of the “culture follows structure” pattern.

Disadvantages? None obvious to us, but there were open questions. Previously, the org-chart reflected single-function groups and personalized responsibilities, which made it easy to find someone for problem X. With cross-functional teams and shared responsibility, this information was not visible in the org-chart anymore. How would other BMW Group departments, which remained in a traditional organizational setup, communicate with ADD?

Further, how to escalate and to whom, when the responsibilities become shared and the organizational structure detached from the product architecture?

Existing LeSS guides can address those questions—for example, Leading Team [3, p. 308] who commit to a long-term topic, for example, collaboration with an adjacent department. Since ADD did not experience those practices before, it was hard to imagine how they would work out.

We chose to leave those questions open and answer them using inspect & adapt.

The advantages were so important to us that we decided to start with this setup.

Step 2 - Set up a PO Team

Who should be the Product Owner? As described in the guide Find a Product Owner Given Your Type of Development [3, p. 173], the first step in finding a PO is to know your development type.

On the one hand, our product—AD—is part of a larger product, the car. In that sense, it was like internal component development. On the other hand, the paying customer needs to add the AD feature to the car configuration and pay extra.

The pivotal point was that the original vision, first set by the head of ADD, was to also offer AD as a separate Autonomous Driving Platform (ADP) to other automobile OEMs. In those ways, it was an external product itself.

For external products the LeSS guide Who should be Product Owner? [3, p. 173] recommends looking for a PO in the Product Management department, such as head of Product Management. Further, the guide defines:

As Product Owner, you have the independent authority to make serious business decisions, to choose and change content, release dates, priorities, vision, etc. Of course, you collaborate with stakeholders, but a real Product Owner has the final decision-making authority. [3, p. 175, emphasis added]

Several factors constrained the PO choice.

The BMW Group had (and still has) a wide range of products, consisting of complex systems. The development and maintenance of which involve tens of thousands of people. The company’s structure reflected the car’s sub-systems, which increased its complexity and fragmentation over the years, especially with the increasing importance of software in each sub-system.

Therefore, no one has the required independent authority to make or change serious business decisions, not even the CEO. Instead, all serious business decisions are made jointly in committees. Therefore, we knew that the independent decision-making authority of our future PO would be somewhat limited.

There were two rationales for choosing a PO from within ADD: (1) the vision of offering the ADP to other automobile OEMs and (2) the fact that LeSS was being adopted at ADD, not at the whole BMW Group scale.

The head of a previously-existing department was already responsible for all ADAS and AD customer offerings; he also held the budget to develop them and decided how to spend it. In the sense of independent decision authority, he had, not the ultimate, but a lot of it. Of course, he needed to align with stakeholders and consider the entire BMW Group’s product range when making decisions. This person became the PO. The APOs were recruited from different parts of ADD.

Unfortunately, as will be explored later, “a lot of” the authority was not enough to establish a properly-structured and prioritized Product Backlog.

The PO and APOs formed the PO team.

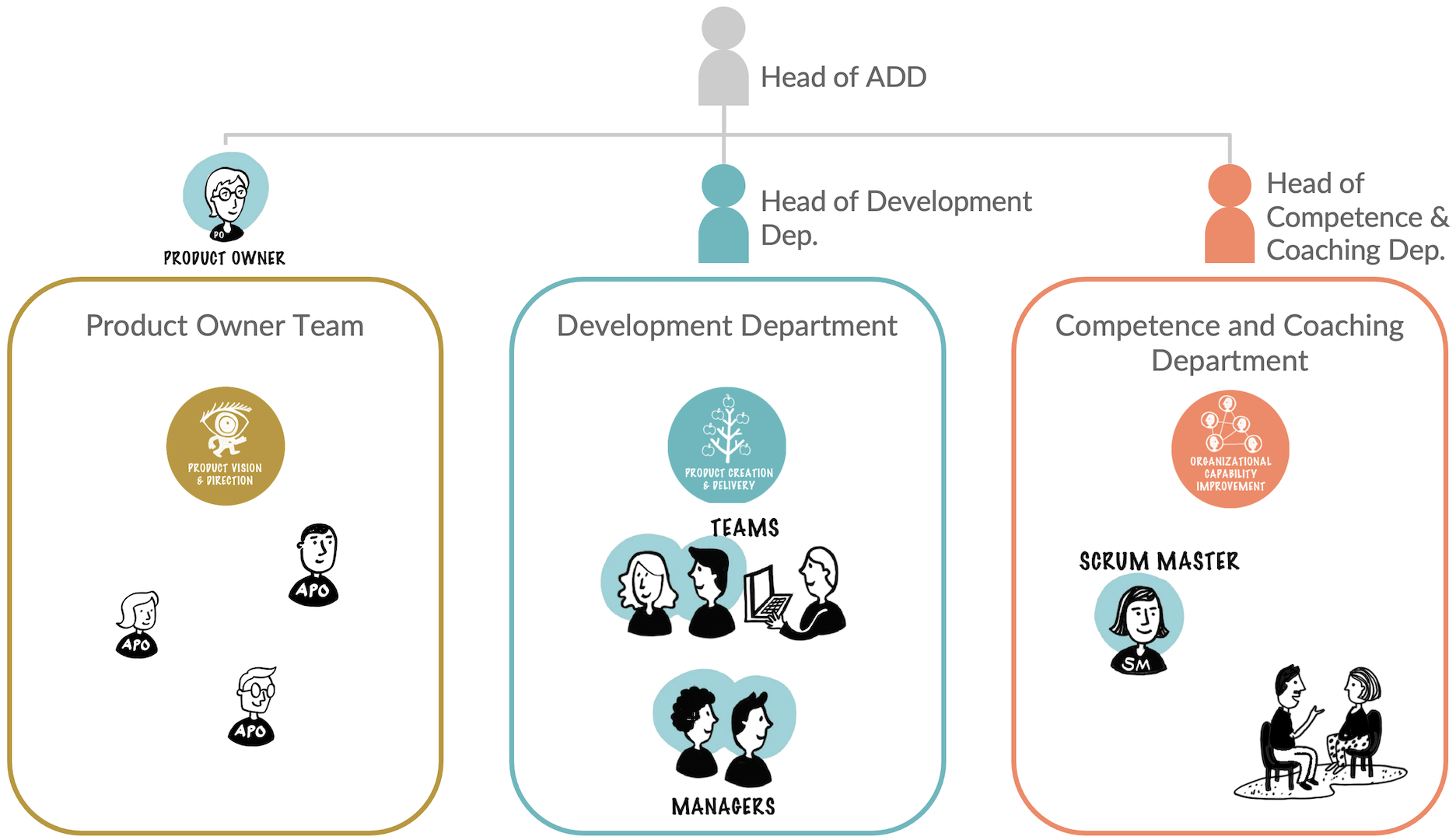

Step 3 - Set up a Competence and Coaching Department

Software is created by people. Improving people improves products. [3, p. 111]

Relentless training and coaching are necessary to achieve mastery in any aspect to improve the product. To support this idea, we created a Competence and Coaching department, as described in the guide Organizational Structure for LeSS Huge [3, p. 111]. It consisted of Scrum Masters, technical coaches, and process-related staff, such as industry-standardization experts.

Why were the Scrum Masters in this department? The Scrum Masters’ responsibility is to teach Scrum (and LeSS) and how to derive value with it, coach the teams, the (A)PO, the line managers, and the whole organization applying it, and last but not least, to act as a mirror. This sort of coaching, especially when acting as a mirror, requires everyone to be on the same conceptual level as the Scrum Master. It is even more critical when previous career paths and grading of individuals influence the perception of different roles and their hierarchy levels.

The typical case at the BMW Group is that the higher the salary grading, the higher the person is in the hierarchy. The grading usually comes with experience and demonstrated skills. Most Scrum Masters had lower grading than APOs and line managers. This raised two questions:

- How will the Scrum Masters perceive and approach the higher graded APOs and line managers when coaching?

- How will the APOs and line managers perceive the “less experienced” (based on their grading) Scrum Masters?

And let’s also add the IPA (individual performance appraisal) to the coaching perspective. One’s direct line manager conducts the yearly IPA. It results in changing one’s grading and salary. Further, it is up to the line manager what data they use for the performance appraisal.

Consider the following hypothetical situation. Suppose a few teams and their Scrum Master have the same line manager. The Scrum Master observes that anti-patterns concerning self-management underpin the line manager’s behavior. What will the Scrum Master do?

- Will the Scrum Master act unbiased as a mirror towards the line manager and make this behavior transparent, risking hurt egos and risking an adverse IPA. Or? …

- Will the Scrum Master accept this behavior mostly or entirely favoring a better IPA for herself as a Scrum Master?

During the discussion of the new processes and the organizational structure, especially the Competence and Coaching department, we reasoned that most Scrum Masters would be biased and would choose the second option. But we wanted to create an environment where Scrum Masters could act as fearless and as unbiased as possible.

Further and considering the above, BMW Group employees were not accustomed to directly talking to higher management without consulting their direct manager beforehand. Therefore, the risk that top-management would get filtered information instead of the real picture from Scrum Masters was considered harmful.

To address these problems and create an environment where Scrum Masters can carry out their job as free as possible, we explicitly wanted the Scrum Masters to have a different line manager than team members. This decision led us to place the Scrum Masters in the Competence and Coaching department.

The Result

The resulting organizational chart looked as shown in Figure 15.

There were three main departments within ADD. The PO, APOs, and their supporting staff comprised the Product Owner department. All Product Developers and line managers were in the Development department. And the Competence and Coaching department contained all Scrum Masters, technical coaches, and additional industry-standardization experts.

Those three departments together sourced the Requirement Areas. APO from the PO department, the teams from the Development department, and the Scrum Masters from the Competence and Coaching department.

A New Age—the First Requirement Area—Begins

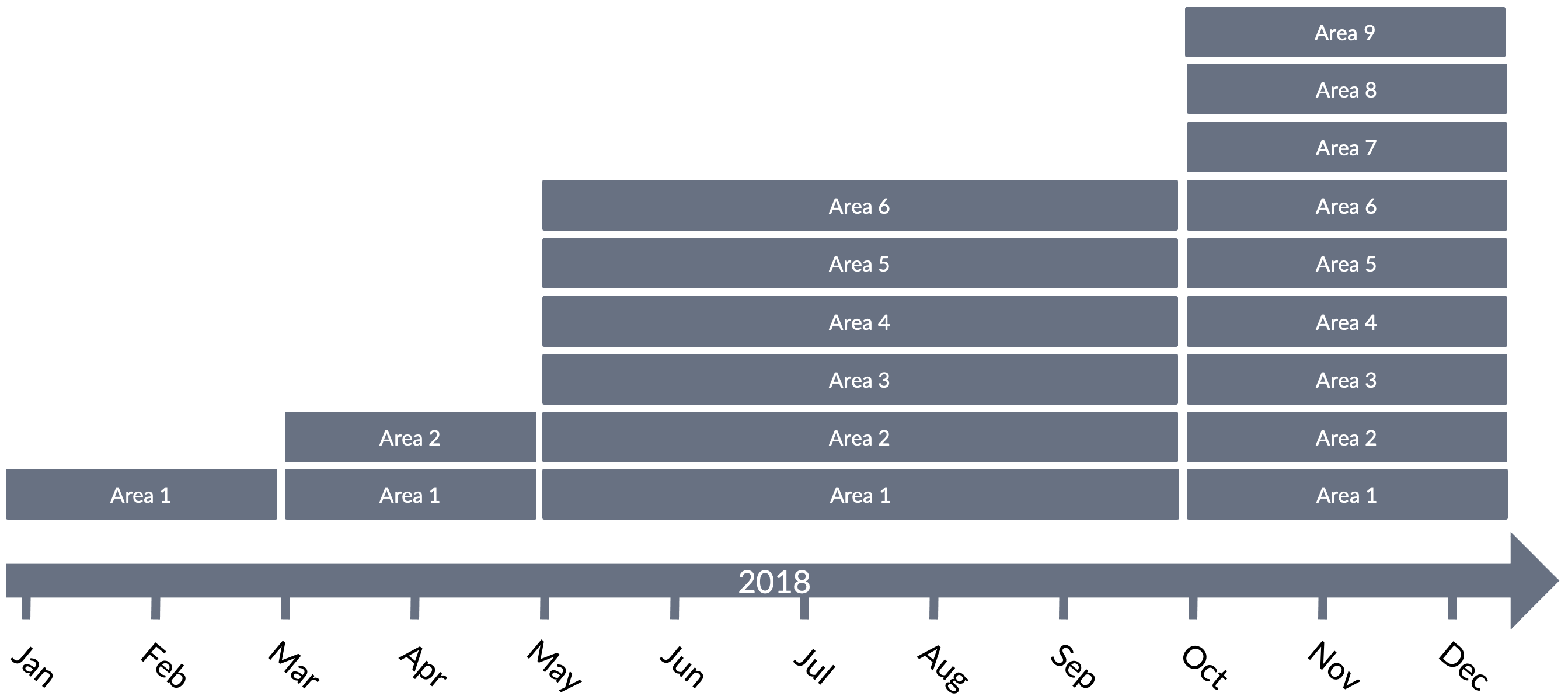

The first of the Three Adoption Principles [3, p. 55]—Deep and Narrow over Broad and Shallow—describes that LeSS should preferably be adopted in one product group well, instead of applying LeSS in many groups poorly. In case of LeSS Huge, LeSS adoptions should start with one Requirement Area and reach a good state before further scaling.

Since this is a LeSS Huge case, ADD followed the principle described above, and the LeSS adoption started with one Requirement Area.

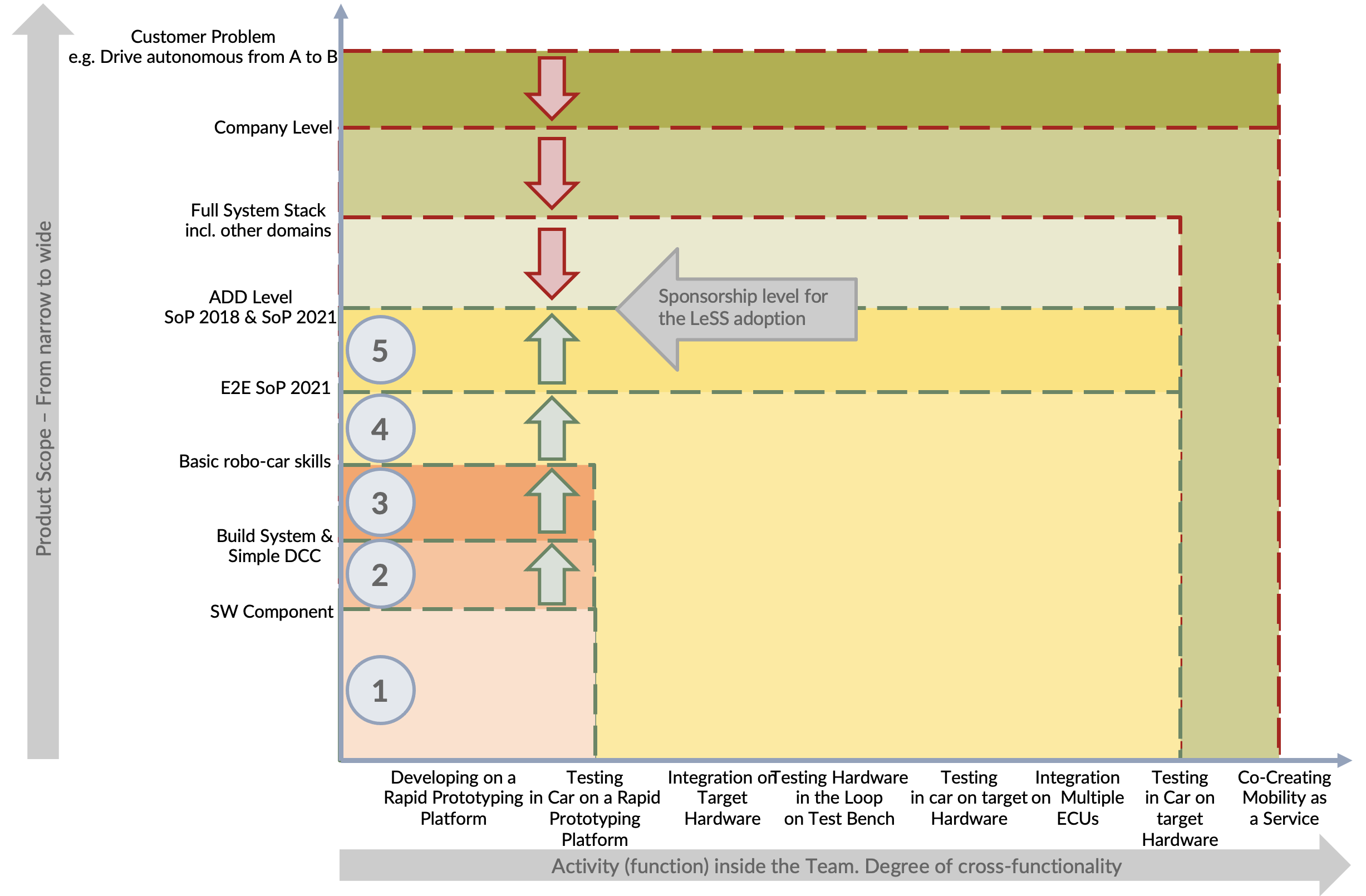

Figure 16 gives a visual scheme of the Requirement Areas’ scope as the LeSS adoption grew. The X-axis represents the cross-functionality of the teams. It shows the level of difficulty. The actions on the right are not a composition of the ones on the left. Developing on a rapid prototyping platform and testing in a car is simpler than integrating and testing the same software on the target platform and in a car. Expanding the scope to multiple ECUs increases the complexity and difficulty a team has to face. Including the co-creation of mobility as a service means working on the whole system, which is impractical, at least today.

The Y-axis shows the product scope, which ranges from a single component to a customer problem.

The starting point was component-based development on a rapid prototyping platform (step 1 in Figure 16), far away from the full product scope.

The focus area of the first Requirement Area needed to include the next step towards cross-functional Feature Teams. It was the following:

- develop a build system sufficient for scaling and adding further Requirement Areas

- simple Dynamic Cruise Control (DCC) as it involved only a few SW components

Step 1 in Figure 16.

Prerequisites and Constraints

Another principle of the Three Adoption Principles [3, p. 55] is to use volunteers.

Use volunteers! True volunteering is a powerful way of engaging people’s minds and hearts. [3, p. 58]

The intention was to start small with volunteers.

At this point, managers’ education consisted of the 1-day introduction to LeSS, Craig’s Readings Preparing for LeSS for Executives, and coaching by Mark Bregenzer. Certified LeSS Executive (CLE) courses took place later, together with Certified LeSS Practitioner (CLP) courses of the first Requirement Area’s participants.

Setting up the first Requirement Area was constrained as follows.

- The size of the first Requirement Area should have been around 70 people.

- The transitioning process to the first Requirement Area had to start at the beginning of August, which meant during the summer school holidays.

- Functional managers of existing functional/component teams were required to temporarily live a double role when transitioning into the LeSS organization. Those would be (1) a line manager in a LeSS organization and (2) a functional manager in the previous organization. This setup would ensure that employees not yet joining the LeSS organization remain with their functional manager.

Parallel Organization

Constraint #1 and the size of ADD (around 800 people) led us to have a parallel organization as described in the respective guide [3, p. 74]. Looking at Figure 16 makes it clear that the scope of the build system and simple DCC (step 2) would be in the LeSS organization. Everything else (steps 3, 4, and 5) would need to remain in the former organizational structure to ensure stable delivery and stable interfaces to the outside of ADD and BMW Group. Figure 17 visualizes the notion of LeSS, non-LeSS organization, and people working for SoP 2018.

The parallel organization and the concept of “only volunteers should join the first Requirement Area” resulted in the third constraint.

Fake Volunteers

As mentioned in the section Product Definition, ADD had two major milestones, SoP 2018 and SoP 2021. The people working on SoP 2018 remained in the former organization to ensure the release; they could not join the LeSS organization. Consequently, nearly all product developers, who delivered a car to series production at least once in their life, were not available for the first Requirement Area. This thinking in projects and, as a repercussion, still organizing people around work restricted the pool of available people with the required skills for successful product development in this context. See Organize by Customer Value [3, p. 78] for more information on the topic of organizing people around work vs. work around people.

Further, the beginning of August was also the beginning of the summer school holidays in Bavaria, Germany (see constraint #2). At this time, people with families were on their summer holidays, which reduced the pool of available people even further. The resulting pool of possible volunteers consisted mainly of long-term researchers who never developed a car to the production stage, people who freshly joined ADD, and few experienced key players.

The shortage of available people, combined with the demand to start the LeSS adoption with eight teams in the first Requirement Area, led to forcing people to become “volunteers.” The order of actions before the first Requirement Area amplified this effect. First, people from the group of potential volunteers volunteered—in some cases, with a little push. Second, after managers provided a list of “volunteers,” they immediately started with CLP classes to educate people on LeSS and give them an idea of what it means to work in a LeSS organization.

Observations during CLP classes showed that some “volunteers” were poorly informed and had little understanding of what it means to work in a LeSS organization. It was the time when the “volunteers” understood what they volunteered for. Some people did not like what they learned. They did not want to be part of the first Requirement Area and became prisoners of the system.

The guide Getting Started [3, p. 59], advises the opposite order—step 0: educate everyone first, before volunteering. That wasn’t done.

After the Start—Revisit Parallel Organization

Before the LeSS adoption at the BMW Group, managers were usually involved in deciding what the actual work was and how to do it. Further, they conducted individual performance appraisals (IPA) and other line manager related tasks, for example, escalations with vendors and organizational changes. Let’s define this type of manager as a traditional manager.

In LeSS, a Product Owner is responsible for the vision of a product and optimizing its impact by prioritizing the Product Backlog—the What. The teams, and only the teams, decide the How of turning the features or needs into a product. The work of both roles is overlapping intentionally. They should support each other.

The existing paradigm at ADD—having clear lines of responsibility—led to the understanding that the duties or tasks of those roles are mutually exclusive. It became: a Product Owner decides on the What, and teams decide on the How.

Regular Scrum, and LeSS in this regard, don’t define the role of a line manager. What should line managers do?

… the role of management changes significantly from managing the work to creating the conditions for teams to thrive … [1, p. 241].

In other words, their role is to improve the value-delivery capability of the organizational system.

ADD defined the responsibilities for the LeSS organization precisely this way. The Product Owner department was responsible for the what. The line managers’ roles in the Development department was to improve the delivery capability of the organizational system, and the teams decided on the how.

Constraint #3 (see Prerequisites and Constraints) specified that a manager transitioning from a traditional manager to a line manager in the new organization would temporarily need to have a double role. The first would be their previous role as a traditional manager. The second would be their new line manager role. This dual role situation would persist as long as the prior group’s subordinates remained in the non-LeSS organization. In other words, a manager who is part of the LeSS organization would still carry out traditional management, deciding on the what and how, in the non-LeSS organization.

The double role setup would violate the distinction of product ownership, line management in LeSS, and traditional management. The concerns about the boundary violation of the roles and organizations led to a rejection of constraint #3. Consequently, the remaining people in the non-LeSS organization became manager free, and no one coordinated the what and the how for them—an unusual situation for those people.

Further, most key players with full system knowledge, if available, transited to the first Requirement Area.

The sum of those circumstances made the rest of the ADD organization strongly dependent on the LeSS organization and they could not deliver without the people in the LeSS organization anymore.

Simultaneously the LeSS organization focused on increasing its delivery capability as a Requirement Area. But, the delivery capability of the entire group working for SoP 2021 decreased, and interfaces to the rest of the BMW Group weakened. Why? Mainly because approximately 250 people in the non-LeSS organization lacked an understandable structure and were lost. Many people stopped doing whatever they were responsible for.

Further, some people of the LeSS organization focused so much on the Requirement Area that they dropped communication and interfaces to the rest of the organization. The pressure for finding a solution increased rapidly, and the lead coach (the first LeSS coach and trainer in this LeSS adoption) became heavily involved in helping to find one. Additional LeSS coaches were engaged in continuing coaching of the first Requirement Area.

The people of the non-LeSS organization needed to work with their colleagues from the LeSS organization. Usually, because someone needed help on topic X, and the topic X expert was in the first Requirement Area. But both groups had significantly different ways of working. “We want to do X in our cross-functional team” vs. “we want to split X across several single-function teams.” Explanations of why the people in the LeSS organization wanted to approach and solve things in different ways led to heated discussions and a higher tension between both groups. Both groups did not speak the same language any longer.

Based on this insight, the CLP classes took place independently of the actual transition into the LeSS organization. The entire ADD received CLP classes within one year. However, by the time the people transitioned into a LeSS organization, their knowledge from CLP classes faded, which created further difficulties in the new Requirement Areas.

Adding More Requirement Areas

Activities such as getting the LeSS organization up and running, creating a solution for the people in the non-LeSS organization, clarifying which legacy code should be part of future development, and many other issues absorbed lots of time and energy. Therefore, progress was rather slow.

There was eagerness for expanding the LeSS organization and starting a second Requirement Area. A few factors motivated it. First, there was a strong desire to become better. It seemed that transitioning people from the almost structureless non-LeSS organization to the LeSS organization would resolve some issues and soothe the pain. Second, the majority of people from the non-LeSS organization who participated in a CLP course were self-motivated to join the LeSS organization as fast as possible. Third, the ADD needed to demonstrate features to their stakeholders and the press. Thus, it was natural that the Senior VP of ADD wanted to see and experience feature increments in the car.

It is worth noting that it is necessary to fulfil some conditions to keep a LeSS organization healthy, especially when adding teams. Those are:

- A common structure for the Product Backlog of all teams and Requirement Areas

- A working build system which ensures fast feedback

At this stage, the Product Backlog of the first Requirement Area started mutating to a multi-level, tree-like requirements set, introducing dependencies between items, which obscured the overview of work to be done, the direction to go, and burdened prioritization already for only one Requirement Area. The Product Backlog started to deviate from the most Product Backlog related guides, especially from Don’t “Manage Dependencies” but Minimize Constraints [3, p. 198] and Three Levels Max [3, p. 222].

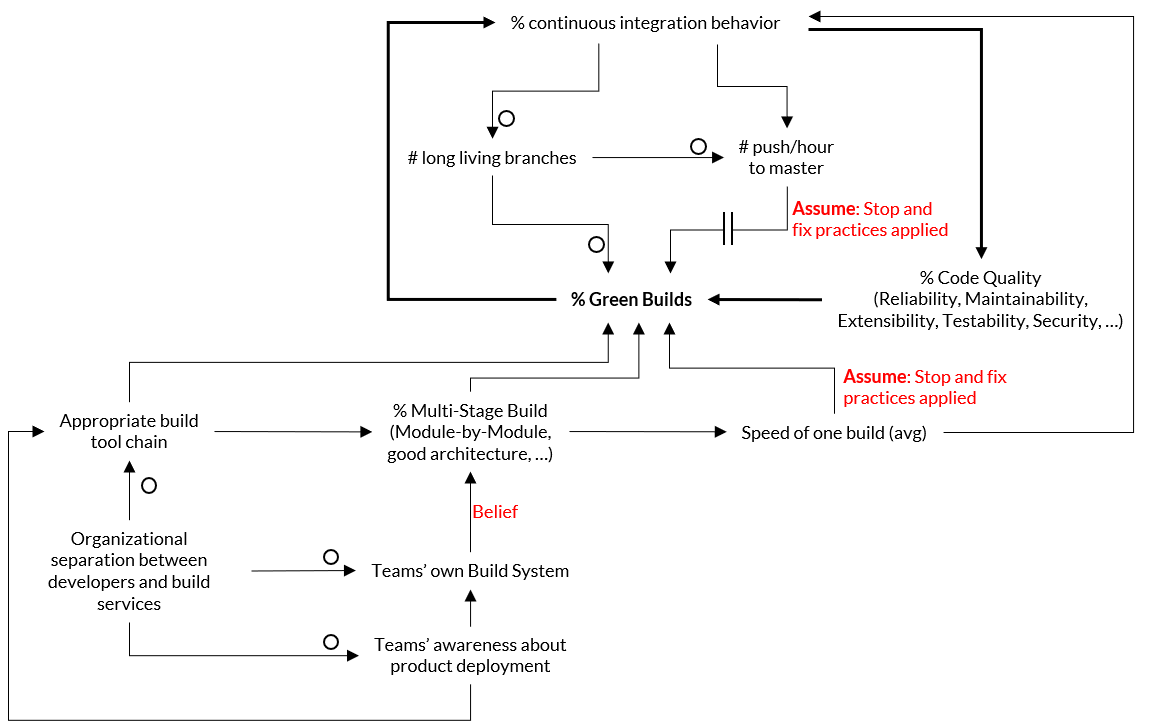

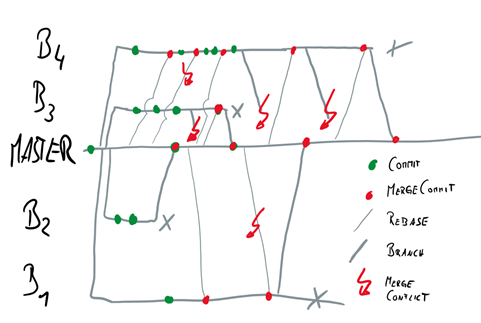

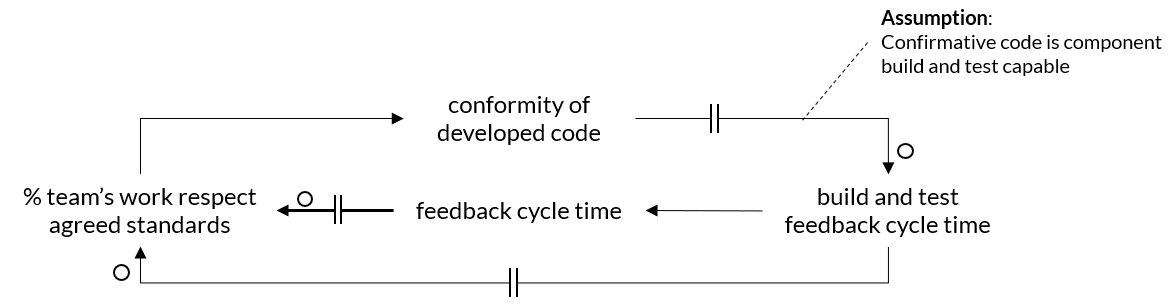

Before the LeSS adoption two “project groups” had created prototype code for some aspects of autonomous driving; the two sets of experimental code contained lots of duplication and inconsistencies across them. To “speed” things up (another quick fix), the entire legacy code from these two bases was merged to the new master branch, with little automated testing, leaving the feature and code coverage at an insufficient level (for more details see Merging Repositories). Consequently, shared code ownership became significantly more difficult. The build system and infrastructure were not ready for this structure and load. The whole system became slow, and feedback times increased significantly. As a consequence, trunk-based development with fast feedback cycles became impossible (more on this topic in the Technology View chapter).

The second Requirement Area kicked off with a broken backlog and build system. And the scope for the LeSS organization expanded to all software components and sensors, yet still being developed on only the rapid prototyping platform (step 3 in Figure 16).

To expand from one Requirement Area to many while sustaining transparency about item priorities in the Product Backlog, it must have a common structure for all Requirement Areas. It enables the PO to better grasp what’s going on, and to prioritize and change teams between Requirement Areas—a quality of organizational adaptiveness. But, the tool, which was used as an electronic Product Backlog, and the people using it, created obstacles. Combined with the obscure multi-level, tree-like requirements set in the Product Backlog, its structures between Requirement Areas (existing and planned) began to diverge at about this time—a local optimization. See also Guide: Tools for Large Product Backlogs [3, p. 210].

Unfortunately, even with these clear weaknesses in place, adding new Requirement Areas continued for the next few months (see Figure 18).

With each step, the scope of the LeSS organization expanded. Adding four Requirement Areas expanded the scope to step 4 represented in Figure 16. With all nine Requirement Areas, the scope reached its maximum, the entire context of ADD (step 5 in Figure 16), yet myriad weaknesses underlay this too-rapid expansion.

Numerous experiments were necessary to find a meaningful scope for each Requirement Area. It took several restructurings, inspect & adapt cycles. During those restructurings, the flexibility of a LeSS structured organization became visible. Since Requirement Areas were not part of an organizational chart or unit, the restructuring process was quick. The fastest restructuring of Requirement Areas (inception until complete implementation), happened within one week.

That was the good news: an adaptive organization. But the bad news was that a key driver for this frequent restructuring was expanding too fast.

Although a LeSS Huge organizational structure allows such flexibility, it is intended to accommodate changing priorities in the customer-centric view, and it comes with some switching costs. Due to interrupting evolved inter-team relationships and established collaboration within one Requirement Area, and the non-trivial domain learning required for teams moving to a new area, frequent restructuring of Requirement Areas has issues.

Retrospective On The Timeline View

Adjusting organizational structure is relatively easy, but changing mindset takes time, discussion, introspection, and learning. [1, p. 229]

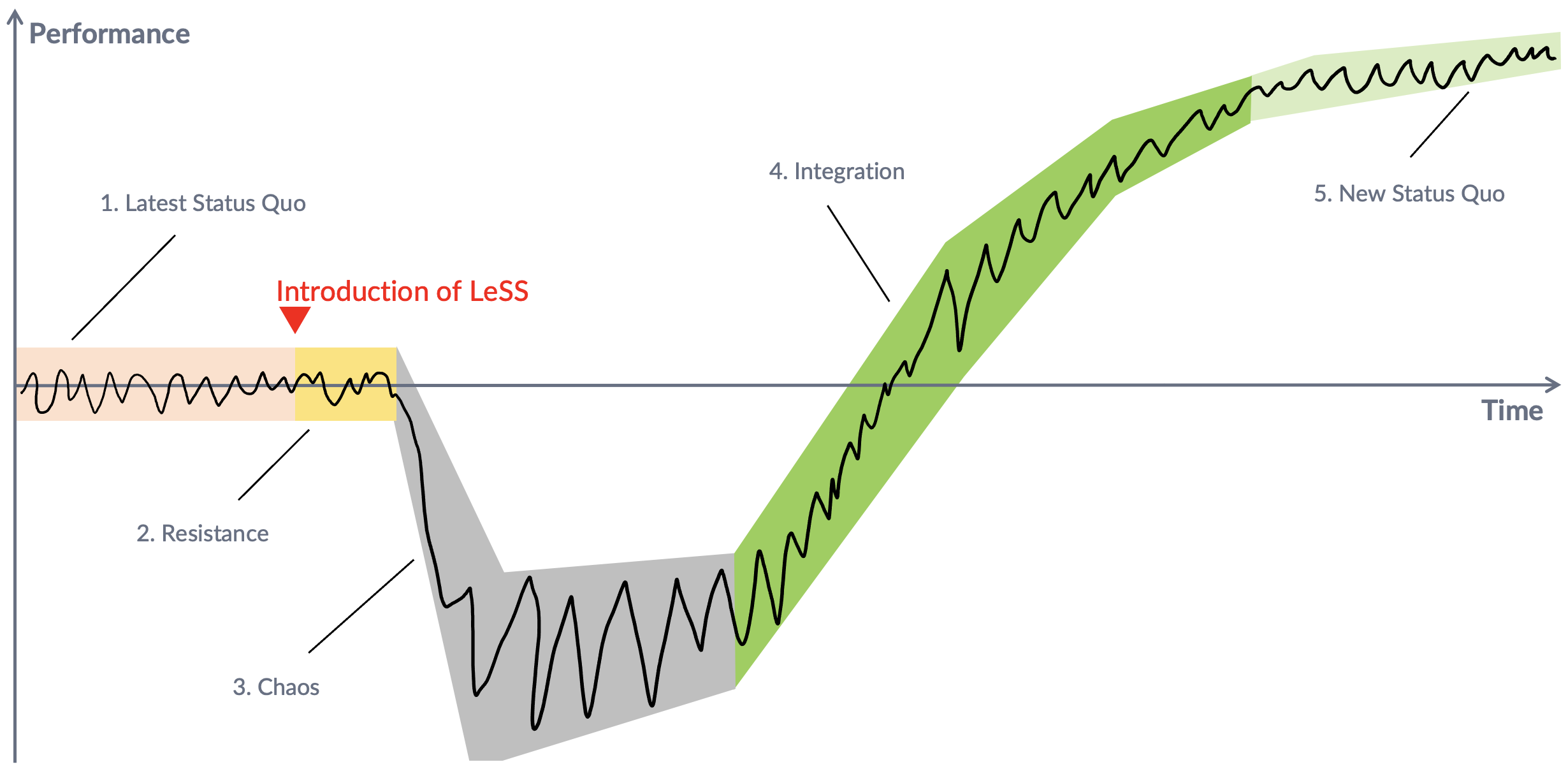

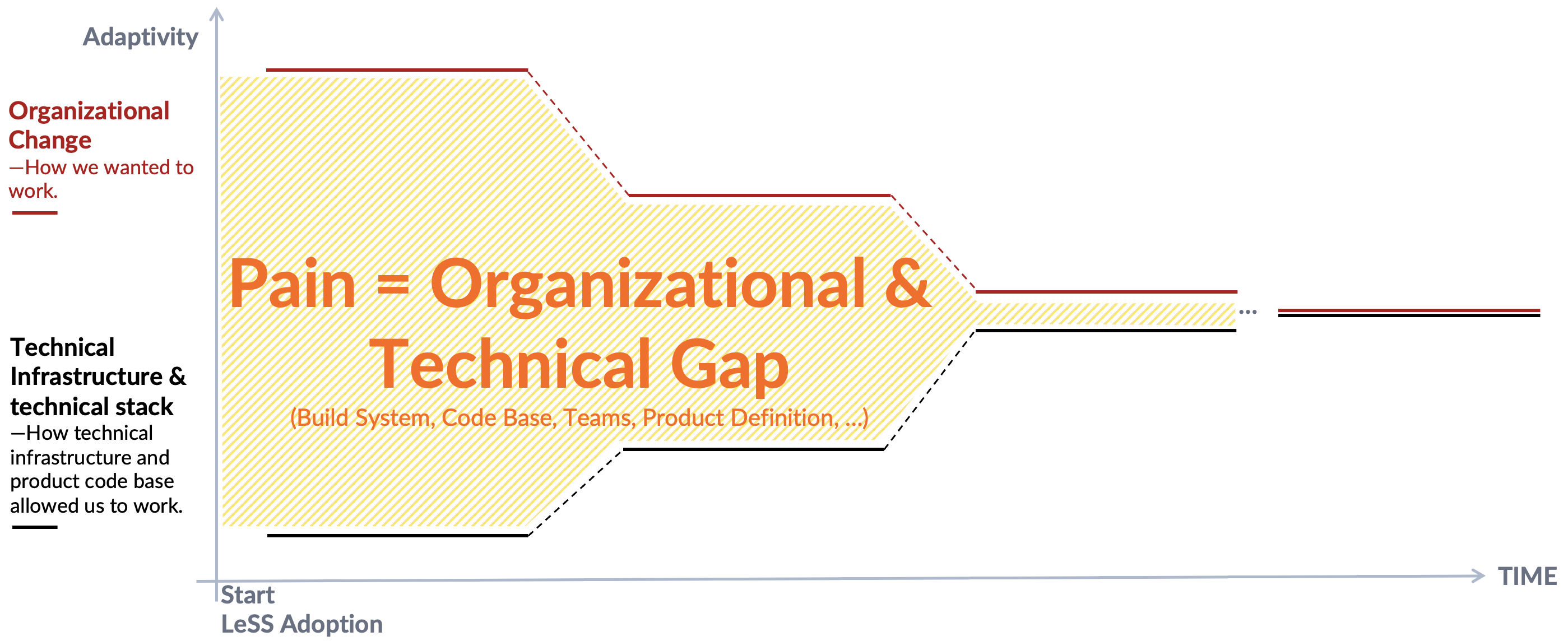

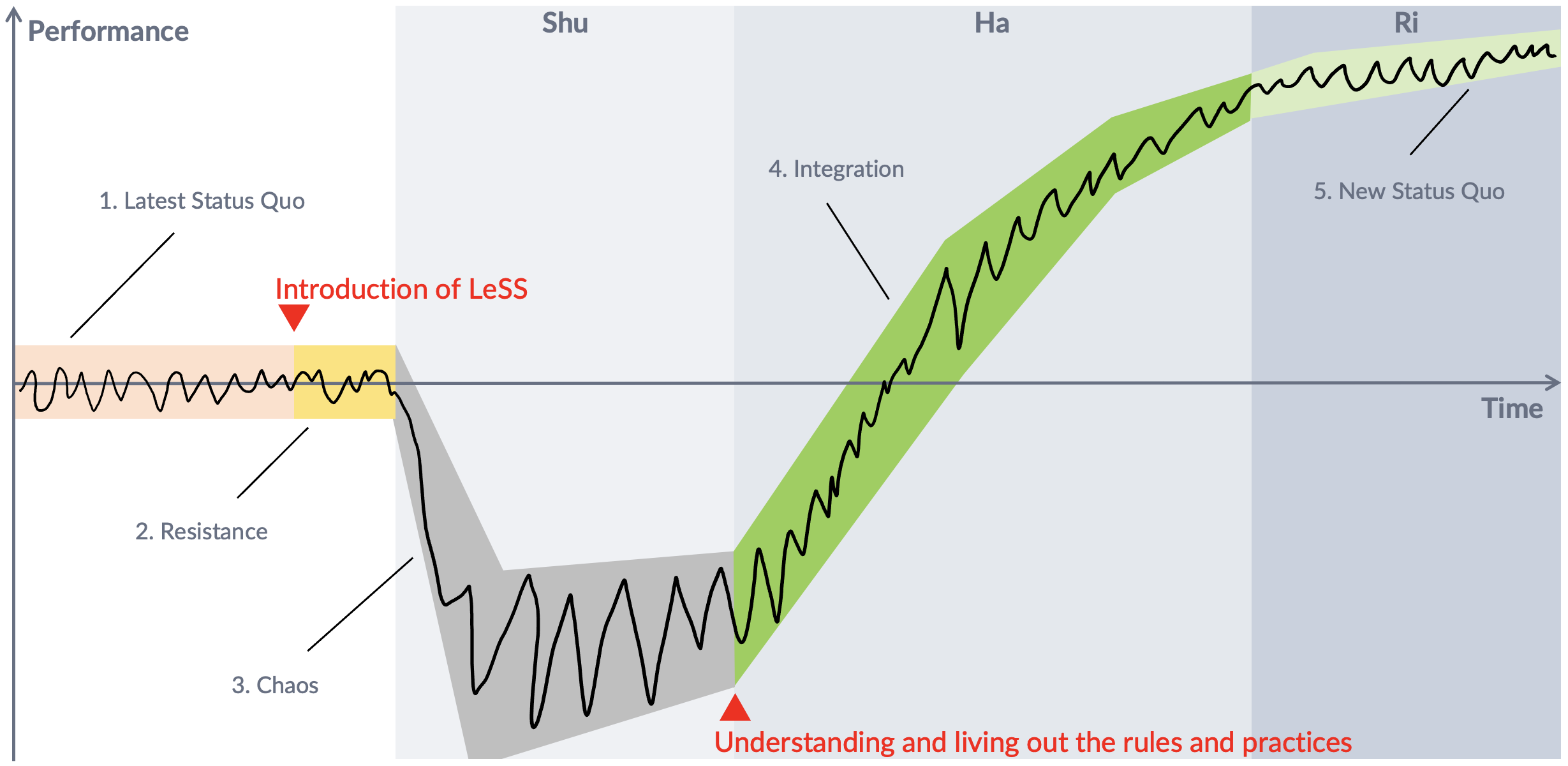

The BMW Group’s LeSS adoption can be visualized with the help of the Satir change model. Figure 19 shows the journey to the current state and how it could look like in the future.

The journey consists of 5 phases. This retrospective view elaborates on the Chaos phase only.

After introducing LeSS, ADD entered this phase quickly! Cognitive biases and the system all humans are in influence our mental models and, therefore, our behavior. Craft mistakes and active sabotage were its effects, leading to the situations described in this report.

The question is: Could the magnitude of the chaos have been minimized or even avoided?

Probably, it could have! And so perhaps you the reader can benefit from some lessons learned. This retrospective view, covering two years after the original steps towards LeSS, exposes causes of the painful dynamics and proposes ways to prevent or minimize them.

The Product Development System

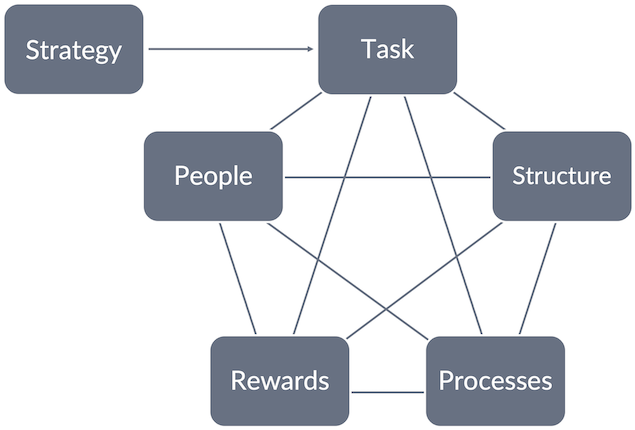

Let’s elaborate on what the product development system is, using Jay Galbraith’s organizational design framework—the Star Model™ (see Figure 20).

Craig Larman and Bas Vodde observed in their book Scaling Lean & Agile Development that a Scrum or LeSS adoption directly alters the processes and structural elements. In ADD’s case, precisely those elements were focused on when preparing for the LeSS adoption.

Structure and processes are only two parts of an organization’s design, and often too many efforts are spent on just them and too little on the other elements.

Structure is usually overemphasized because it affects status and power… [14, p. 4]

The Star Model elements are highly interwoven and have influential forces on one another, which together influence the behavior, culture, and performance of the organization. Therefore, alignment between all elements is crucial for an organization to be effective. Otherwise, the organizational capability decreases. Galbraith put it this way:

For an organization to be effective, all the policies (elements in the Star Model™) must be aligned and interacting harmoniously with one another. [14, p. 5, explanation in parenthesis added, emphasis added]

This retrospective analysis is structured using the Star Model elements.

Strategy & Task

Effective team self-management is impossible unless someone in authority sets the direction for the team’s work. [12, p. 62]

Despite a LeSS introduction and decision to manage product development as product development, the reality felt like project development.

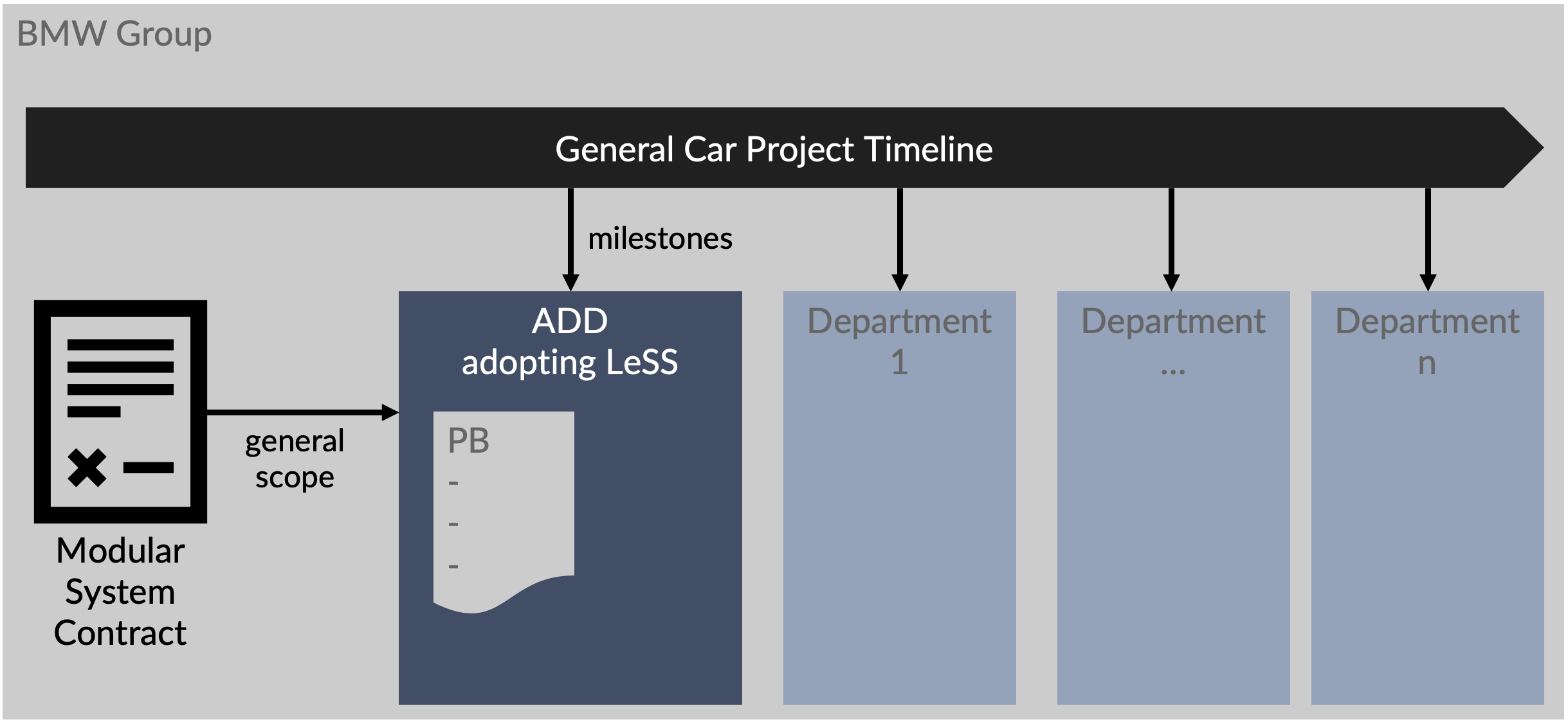

The BMW Group had (and still has) a Product Management department, which accommodates people who plan and manage the entire life-cycle, from idea to development to maintenance, of all vehicles that the BMW Group offers. This department sets up modular systems contracts with other departments that develop car parts. Such a contract usually covers a set of different vehicles, their release dates, general scope, budget, and aims at high reuse of the components/systems the departments develop.

Before the LeSS adoption, such a modular system contract (an actual document) was signed between the ADD and Product Management departments.

The traditional automotive industry still does long-delayed integration rather than frequent. Therefore, there was (and still is) a BMW Group-wide general car project timeline, which defined fixed integration steps and other milestones across all involved departments on the way to the start of production so that they can synchronize their work on a slow cycle.

Figure 21 illustrates the setup between the modular system contract, the general car project timeline, and ADD.

Over decades managers conveyed the message that “we need to deliver everything and on time,” meaning the contract’s scope, by the release date agreed upon. The message turned into a mantra, spread and believed in by many people, not just managers. Consequently, the desire to deliver everything was high, and the message continued to spread. Further, this ethos arose in the context of creating electro-mechanical components such as a braking system; which are infinitely less complex, less variable, and less research-oriented than the profoundly hard job of creating AD software.

Interestingly, the people conveying this message ignored the evidence that, at least in the last decade, the product group never delivered “everything” on one given deadline. There usually was an intensive work mode (like a task force), where someone deprioritized less important topics to focus on the mission-critical ones.

Further, the scope described in the modular system contract was, to a degree, negotiable. What was that degree? All the features a customer could experience in the latest car model must also be available in a new model. Therefore, the scope of existing features was a must-have. However, the content of new features was negotiable.

Despite the evidence, those circumstances diminished the acceptance of reducing-the-scope discussions (at least at an early stage), leading to no prioritization because “everything was crucial.” The resulting behavior was “we need everything.” Wishful thinking! Of course, if everything is equally important, everything is equally unimportant. Only one year before the release, deprioritization started—meaning re-negotiations of the scope and date. Such late re-negotiations were—and still are—common and in line with other BMW Group projects; therefore, they were expected.

Another aspect led to an unprioritized so-called “Product Backlog” (so-called since, per definition, a real Product Backlog would be prioritized, providing a clear direction). Most not-really-APOs “APOs” were project managers who had also previously been developers.

The first Requirement Area started with such “APOs” acting as a fake PO because it was only one Requirement Area, and the person who later became the PO was not fully available. Sometime after starting the first Requirement Area, both “APOs” rejected coaching, especially on setting up a real Product Backlog. Why?

To start with, the learnings emerging during the initial coaching sessions were undoubtedly uncomfortable. For example, accepting that the idea of managing the product complexity by splitting it into small parts is an illusion and that instead, empirical control, learning from product experience feedback, and prioritization are a better approach.

And some “APOs” in high power positions refused LeSS coaching from people they saw under their status level—basically all coaches we engaged.

The resulting lack of PO/APO and Product Backlog competence led to a “Product Backlog” full of technical tasks on multiple abstraction layers and many dependencies between them, which was the main impediment for the PO to prioritize the Backlog.

Key point: Most “APOs” could not keep the whole product focus and derive valuable items for the next Sprints. Instead, they tried to split everything into small parts—a decades-of-practice habit and a fear response of forgetting something.

Those circumstances were very convenient for the teams because technical tasks narrowed their focus to just one or two components but didn’t motivate them to learn the customer language, nor to learn across a broader set of components and skills to increase their learning and adaptiveness. In consequence, the so-called “Product Backlog” consisted mainly of technical tasks instead of customer-centric items. The result was two other anti-patterns. (1) Re-prioritization on the product level became difficult—in fact, close to impossible—because technical tasks naturally depended more on each other. And (2) collaboration and coordination opportunities between teams when finding technical solutions for customer-centric problems were hard to find. Why? Because technical tasks typically reflect only a small part of the whole system, for example, one component, but customer-centric items usually span multiple system elements.

Both anti-patterns led to overloaded so-called “APOs.” Some of them acted as single-team “POs,” prioritizing specific team backlogs in their Requirement Area, which reinforced and amplified the downward spiral from a product-requirement to technical-task perspective.

The result? Lack of whole-product focus and prioritization, leading to high busyness and output of completed technical tasks, but very low output of completed customer features, and thus no useful outcome. This typhoon of technical tasks made it impossible for the PO to have a meaningful whole-product overview, to order the so-called “Product Backlog,” which disempowered him and made him dependent on the technically involved “APOs”—he had to believe what the “APOs” told him.

Why didn’t the PO clean up this mess? Why didn’t he enforce a real Product Backlog enabling him to order it? One cause is the lack of time for the job as PO. The person playing the PO role had many other duties; for example, VP of a department, project manager of a project external but adjacent to ADD, and most importantly, he was occupied with the SoP 2018 release. And there are very likely other reasons that remain invisible to us.

It begs the questions of why a “free” PO was not chosen and why we thought an overburdened person could effectively learn and do a complicated new approach?

No-one, at least to my knowledge (Konstantin here), questioned whether or not this person should become PO. He was considered a perfect fit for the PO role by people on all hierarchy levels. Why? Because before the LeSS adoption, he was the VP of the customer offerings department and re-prioritization was in his job’s nature.

Having time to live out the PO role was not considered an issue because he could have delegated other activities to his staff and free himself up.

Therefore, the better questions are: Why did he become overburdened, and why didn’t he receive PO coaching?

To start with, the PO lapsed into a traditional management paradigm. He delegated most of the PO tasks and trusted that his staff would execute them properly.

Further, he knew about the problem of technical tasks “Product Backlog.” But, he decided to support his so-called “APOs” mainly because the “APOs” saw the lead coach as someone who never delivered a car to production, which degraded the coach in the “APO’s” and PO’s eyes. Therefore, the PO trusted his “APOs” more.

… the failure to establish a compelling direction runs two significant risks: that team members will pursue whatever purposes they personally prefer, but without any common focus; or that they gradually will fade into the woodwork … [12, p. 80, emphasis added]

How could this situation be resolved?

The key is to identify who has the legitimate authority for direction setting and then to make sure that that person or group exercises it competently, convincingly, and without apology. Team performance greatly depends on how well this is done. [12, p. 63, emphasis added]

A better approach would have been to free up the PO of other duties, which have little to do with product ownership. Further, replace the so-called APOs with real ones who focus on the product instead of technical solutions.

Further, de-escalation and mediation sessions would probably have been helpful to re-establish PO and APO coaching.

Moreover, a Product Backlog (PB) transformation from SW component-centric and technical tasks to customer-centric features would enable the PB’s prioritization and allow teams to solve real customer problems.

Whole product focus is crucial! Inviting users, paying customers, and subject-matter experts to the Product Backlog Refinement (PBR) sessions would have helped establish a customer language, gain whole product focus, and deliver the ADD product incrementally with evolving customer features rather than completing technical tasks.

How to involve customers in PBR and comply with information-protection policies? It is worth realizing that many of BMW Group employees are also customers. They drive BMW cars and experience the product themselves. The only constraint would be to involve those who don’t understand the technical details and only speak the customer language—for example, people from HR, legal, or procurement.

Structure

The job of managers is to build an environment in which teams continuously deliver and continuously improve. [3, p. 69]

Managers’ role is to improve the product development system by practicing Go See, encouraging Stop & Fix, and “experiments over conformance.” [3, p. 115]

The starting structure allowed a high degree of organizational adaptiveness, which we experienced when reforming Requirement Areas. Since Requirement Areas were not part of an organizational chart or unit, the restructuring process was quick.

The ADD used this benefit to frequently change Requirement Areas, mainly caused by a too-fast expansion of the LeSS organization (see also Adding More Requirement Areas). Why did the LeSS organization expand too fast?

One cause lies in the BMW Group’s traditional career paths, where good hands-on engineers at the top of their technical career became mediocre managers. Consequently, the sunshine to bad-weather managers ratio was high, decreasing the managers’ capability to structure and manage the non-LeSS organization, subsequently leading it to an unhealthy state, which became one strong force to bring the people into the LeSS organization faster.

Another cause—likely related to the previous—was the non-LeSS group’s inability to work independently from the LeSS organization due to a lack of experts, who mainly were in the SoP 2018 project and the LeSS organization. This situation is a consequence of thinking in and organizing people around projects instead of products.

Despite the thoughtful groundwork of organizational structure and striving for self-managing teams and collaboration in communities of practice, people perceived self-management, particularly in communities, as ineffective. This was because of a vast amount of unskillful decisions and weak decision-making, due in part to the lack of experience and ability in decision-making amongst developers (since this was previously done by people in specialist roles and managers) and also in part to the lack of experience and skill amongst the Scrum Masters, who did not effectively coach the teams or communities in participatory decision-making protocols.

As a quick fix, for this and related reasons, senior managers revived C-4 level managers and specialist roles around two years after starting the first Requirement Area. Further, the organizational structure fossilized such that Requirement Areas became official organizational units, which leads to rigid hard-to-eliminate groups instead of adaptive birth/grow/shrink/die Requirement Areas, which are essential within LeSS Huge. Further, official organizational groups reinforce the silo problems. Unfortunately, this insight was either never present or forgotten at ADD, which led to ignoring the guide LeSS Huge Organization.

Avoid having the Requirements Areas be equal to the organizational structure as it leads to them being difficult to change. [3, p. 110]

Let’s elaborate on why many decisions were unskillful, and decision-making was ineffective.

When changing from manager-led to self-managing teams and communities, managers’ and sometimes Scrum Masters’ thinking was, “Either the teams/communities are self-managing, or I need to step in, breaking the self-management.”

Key point: This was a false dichotomy. Instead, it should have been: “I need to help them become self-managing.”

Driven by the fear of breaking self-management, managers left the teams and communities mostly to themselves. Since they had to make decisions, the most inadequate and naive decision protocol became their default, majority voting, another quick fix not seen, and even worse, supported by junior Scrum Masters. The experienced people were a small minority and were outvoted most times. Therefore, most decisions were unskillful and ineffective.

Key point: We failed to establish a skill hierarchy (without specialist roles) and introduce adequate decision-making protocols, such as a quorum of skilled and experienced people makes decisions.

The situation became similar to the one described by Jo Freeman in her article The Tyranny of Structurelessness [15].

… the movement generates much motion and few results. Unfortunately, the consequences of all this motion are not as innocuous as the results’ and their victim is the movement itself. [15]

How could a specialist-role-free skill hierarchy look like?

First, make transparent who has beginner, intermediate, advanced, or expert skills and their fields. Second, ensure that people with advanced and expert skills form a quorum for decision-making and introduce participatory decision-making protocols, such as the Decider/Resolution from The Core Protocols [19].

Third, make the differences between the skill levels transparent so that people know how to advance. Fourth, help people gaining advanced and expert skills. Moving from beginner to intermediate can usually be done by acquiring knowledge. Moving from intermediate to advanced and then to an expert level takes time, where the knowledge gets enriched by the experience.

Processes

Do Continuous Improvement Towards Perfection… Continuously

We wanted to follow the Deep and Narrow over Broad and Shallow [3, p. 55] adoption principle and adopt LeSS step-by-step, one Requirement Area slowly after another. The contract engaging coaches defined a fixed-price package of bringing 70 people into the LeSS organization at a time.

The emphasis on complying with the contract was strong, especially in the beginning. Otherwise, there would be less “value” for the same money—a contract game. This dynamic led to the… prerequisite of having 70 people in the first Requirement Area! Combined with the demand of starting the LeSS adoption at the beginning of summer holidays, and therefore little availability of people, this led to forced “volunteering” (see also Prerequisites and Constraints and Fake Volunteers). Thus, most Requirement Areas started with this number of people.

The contract also contained a project plan—a Gantt chart describing when the LeSS adoption starts and ends. This project plan, based on ignorance of skillful change and improvement, aimed to comply with the purchasing processes and BMW Groups’ policies. Behind the scenes, of course, there was no intention by those understanding adaptiveness for it to be used as an actual project plan.

But of course Murphy’s law came true: senior managers discovered this project plan, and then ADD followed it, mainly because it indicated an end date of a continuous change. Consequently, and this plan is only one cause, the LeSS organization expanded mostly according to plan rather than according to what made sense! See also Adding More Requirement Areas and Structure.

Key point: Continuous Improvement Towards Perfection was seen and run as a project instead of continuously.

Avoid Making Departments or Individuals Responsible For a Special Thing

Whenever an existing process needed adaptation or compliance with industry standards required a new one, most of the time the PO team and the development department delegated these tasks and withdrew themselves (see Figure 15). Why?

One cause is that people were used to working this way. Another is that the important idea of those who use and live the processes make the processes was, to a large extent, not lived.

Key Point: In LeSS, teams are responsible for their processes. It is a direct consequence of having self-managing teams. See Guide: Understand Taylor and Fayol [3, p. 115].

One of the differences between self-managing and manager-led teams is the responsibility for their processes. Self-managing teams own their processes. Since this understanding was lacking at the BMW Group and due to organizational size and dependencies external to ADD, most people rented the processes rather than owned them.

Let’s take a look at the reasons why people did not take responsibility for their processes.

During the first two years of the LeSS adoption, people had doubts about their ability to align with LeSS principles and rules when changing existing or designing new processes. To resolve this situation, Scrum Masters coached LeSS principles and helped to create or improve processes. It is a healthy dynamic.

During the preparation phase, before the LeSS adoption, this dynamic was foreseen. To ensure alignment with LeSS and industry standards, the Competence and Coaching department, which consisted of Scrum Masters and industry-standardization experts, became the official body responsible for processes.

Why did the Scrum Masters allow themselves to get involved in something so obvious that they should not? Due to little Scrum experience in the entire ADD, there was a deeply engraved understanding that Scrum is somewhat a process. As a corollary, there were no masters of Scrum. Instead, there were junior Scrum Masters who did not foresee the dysfunctions the “responsible for processes” label would create.

The official “responsible for processes” label created a mental barrier in people’s minds. People sought approval from the Competence and Coaching department for any changes in any process. After some time, this turned into handing problems over to the Competence and Coaching department and expecting them to drive their resolution.

As a quick fix, the Competence and Coaching department was split into two—(1) A unit of industry-standardization experts and (2) a homogeneous Scrum Master organizational unit. Two functional groups, each with their single-function line manager. This was an example of the “default organizational problem-solving technique. (1) Discover a problem—the blah-blah problem. (2) Create new role—the blah-blah manager. (3) Assign problem to new role.” [3, p. 120]

In the long run, one negative and unforeseen side-effect was that the industry-standardization experts unit ended up creating various unskillful processes for the teams since they had little hands-on experience nor insights. In retrospect, with more focus on the experiment Avoid…Adoption with top-down management support [2, p. 374], we might have been able to anticipate this since it warns of this very problem.

In conclusion, making an organizational unit responsible for processes is counterproductive for human workers in about any context. It is a manifestation of the very basic tayloristic approach of separating work between people who plan and people who mindlessly execute the plan.

Key Point: In fact, “responsible for anything” labels create bottlenecks, delays, hand-offs, various other wasteful dynamics, and, most important, the ownership problem. That is when the psychological connection between the role or group responsible for X and other people owning X gets broken.

The Competence and Coaching department received the “responsible for processes” label for people from other departments to know whom to seek advice from when changing processes. However, this label created an unwanted dynamic.

A more effective means to the same end would be to (1) allow the industry-standardization experts to join teams to gain hands-on experience, and (2) have regular team members be centrally involved in creating the processes.

Rewards

During preparation for the LeSS adoption, coaches strongly emphasized the importance of changing the rewards system (including the salary model) to support the other elements of the product development system.

Specifically, subjective manager-driven promotions and manager-based individual performance appraisals (IPAs) needed significant changes to support self-managing teams. Why?

Manager-driven promotions drive the desire for manager-based IPAs, yet the manager (appraiser) virtually never has the insightful information to skillfully appraise. And then there are biases—conscious and otherwise. Combined with long cycle times (in this case 12 months!) between IPAs, the feedback becomes superficial and unrelated to the individual’s specific behavior. Hence, the feedback quality for the individual’s betterment is highly questionable.

Further, since manager-driven promotions are subjective, people start to believe that promotions are less related to performance but more related to having the “right” relationships and an ingratiating personality. Jeffrey Pfeffer described this dynamic in his worth-reading Harvard Business Review article Six Dangerous Myths About Pay.

This leads to individualism, heroism, and other dysfunctions in an intended self-managing teamwork environment.

At ADD, C-3 level managers, together with the HR department, had the aspiration to change the existing IPA to support teamwork and make the rules for individual career advancements transparent. But they failed.

This situation wasn’t a problem until…

…The next cycle of IPAs. Since nothing changed, people still expected their line managers to conduct their IPA. But! …The elimination of the C-4 level managers increased the span of each C-3 line manager to about 60 employees, who now had many IPAs while at the same time having even less sight and insight.

This dynamic made the already-subjective IPAs even more subjective. Later, an employee satisfaction survey confirmed people’s frustration with this situation and their managers. Urgent improvement was necessary.

As a quick fix senior managers revived managers on the C-4 level to decrease the span and generate a false feeling of objectiveness in the next IPA cycle. Back to the status quo!

Conclusion

When introducing a significant change, such as a LeSS adoption, and changing only the structure and processes, but not reward policies and other elements, the change will fail. It’s a system!

The Star Model™ suggests that the reward system must be congruent

with the structure and processes to influence the strategic direction. Reward

systems are effective only when they form a consistent package in

combination with the other design choices (elements in the Star Model™). [14, p. 4, explanation in parenthesis added]

If upper managers don’t exercise systems thinking, then the system will “revert to mean” simply because everybody knows it. Only changing parts of the system and having high expectations causes pain. It forms the opinion, “We have tried X, it does not work,” and leads to reactive responses, which usually result in quick-fix reactions.

What could be an alternative?

A shared objective is necessary before evaluating alternatives. If the goal is employees’ short-term compliance, then behavioral manipulation is probably the best approach. In this case, it is senseless to work towards self-managing teams because both aims contradict each other.

The next paragraphs assume a shared agreement on the goal of having self-managing teams. To elaborate alternatives, the practices of individual performance appraisal and promotions need some deconstruction.

Individual performance appraisal:

The common two purposes of a performance appraisal are:

- feedback for betterment (improvement and development, e.g., adding new strengths or adding to existing strengths), and

- input for promotion.

Feedback for betterment is supposed to be a two-way conversation, conducted frequently rather than annually, and it is utterly divorced from promotions.

Providing feedback that employees can use to do a better job ought never to be confused or combined with controlling them by offering (or withholding) rewards. [17, p. 185]

It seems foolish to have a manager serving in the self-conflicting role as a counselor (helping a man to improve his performance) when, at the same time, he is presiding as a judge over the same employee’s salary… [18]

In a Scrum environment, the team members and their Scrum Master—who are working closely together and understand in detail each other’s work—have the opportunity to give feedback to each other every Sprint Retrospective. Since this is standard practice, the value of this purpose in IPAs vanishes.

What is left are promotions.

Promotion (and Rewards): a decision (by another party) for someone to be categorized in a new role classification that is considered “higher” and a desirable step. It usually includes a raise in one of the following: salary, power, visibility, prestige, influence, decision authority, recognition, etc.

What is usually interesting to people is not a promotion per se, but what comes with it, and promotions usually offer different types of rewards. Frederick Herzberg categorized some of them in his Harvard Business Review article “One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?” into two categories: (1) hygiene factors and (2) intrinsic motivators [16]. According to Herzberg, a bad implementation of the hygiene factors leads to job dissatisfaction. However, getting those right does not lead to job satisfaction. Instead, it leads to no job dissatisfaction. Intrinsic motivators are the ones which lead to job satisfaction.