Introduction to LeSS

(this is chapter 2 of the book “Large-Scale Scrum: More with LeSS”)

There are two ways of constructing a [design]:

One way is to make it so simple that there are obviously no deficiencies,

and the other way is to make it so complicated that there are no obvious deficiencies.

C.A.R. Hoare

One-Team Scrum

Scrum is an empirical-process-control development framework in which a cross-functional self-managing Team develops a product in an iterative incremental manner. Each timeboxed Sprint, a potentially shippable product increment is delivered and, ideally, shipped. A single Product Owner is responsible for maximizing product value, prioritizing items in the Product Backlog, and adaptively deciding the goal of each Sprint based on constant feedback and learning. A small Team is responsible for delivering the Sprint goal; there are no limiting single-specialized roles. A Scrum Master teaches why Scrum and how to derive value with it, coaches the Product Owner, Team, and organization to apply it, and acts as a mirror. There is no project manager or team lead.

Empirical process control requires transparency, which comes from short-cycle development and review of shippable product increments. It emphasizes continuous learning, inspection, and adaptation about the product and how it’s created. It’s based on understanding that in development things are too complex and dynamic for detailed and formulaic process recipes, which inhibit questioning, engagement, improvement.

In the Scrum Guide and Scrum Primer, the emphasis is for one Team; the focus is not many Teams working together. And that naturally leads to thinking about large-scale Scrum.

LeSS

LeSS is Scrum applied to many teams working together on one product.

LeSS is Scrum—Large-Scale Scrum (LeSS) isn’t new and improved Scrum. And it’s not Scrum at the bottom for each team, and something different layered on top. Rather, it’s about figuring out how to apply the principles, purpose, elements, and elegance of Scrum in a large-scale context, as simply as possible. Like Scrum and other truly agile frameworks, LeSS is “barely sufficient methodology” for high-impact reasons.

Scaled Scrum is not a special scaling framework that happens to include Scrum only at the team level. Truly scaled Scrum is Scrum scaled.

…applied to many teams—Cross-functional, cross-component, full-stack feature teams of 3–9 learning-focused people that do it all—from UX to code to videos—to create done items and a shippable product.

…working together—The teams are working together because they have a common goal to deliver one common shippable product at the end of a common Sprint, and each team cares about this because they are a feature team responsible for the whole, not a part.

…on one product—What product? A broad complete end-to-end customer-centric solution that real customers use. It’s not a component, platform, layer, or library.

• Background •

In 2002, when Craig wrote Agile & Iterative Development, many believed that agile development was only for small groups. However, we both (Craig and Bas) became interested in—and got increasing requests—to apply Scrum to large, multi-site, and offshore development. So, since 2005 we have teamed up to work with clients to scale up Scrum. Today, the two LeSS frameworks (smaller LeSS and LeSS Huge) have been adopted in big groups worldwide in disparate domains:

- telecom equipment — Ericsson & Nokia Networks

- investment and retail banks — UBS

- trading systems — ION Trading

- marketing platforms and brand analytics — Vendasta

- video conferencing — Cisco

- online gaming (betting) — bwin.party

- offshore outsourcing — Valtech India

In terms of large, what’s a typical LeSS adoption case? Perhaps five teams in one or two sites. We’ve been involved in adoptions of that size, of a few hundred people, and up to a LeSS Huge case of well over a thousand people, far too many development sites, tens of millions of lines of C++, with custom hardware.

More LeSS Learning

To help people learn and based on our experiences with clients, in 2008 and 2010 we published two books on scaling agile development with the LeSS frameworks:

- Scaling Lean & Agile Development: Thinking and Organizational Tools for Large-Scale Scrum — explains the thinking, leadership, and organizational design changes.

- Practices for Scaling Lean & Agile Development: Large, Multi-site & Offshore Product Development with Large-Scale Scrum — shares hundreds of concrete experiments for LeSS, based on our experience with clients; experiments in product management, architecture, planning, multi-site, offshore, contracts, and more.

This book—Large-Scale Scrum: More with LeSS—is the third in the LeSS series, a prequel and primer. This book synthesizes, clarifies, and highlights what’s most important.

Besides these books, see less.works for online learning resources (including book chapters, articles, and videos), courses, and coaching.

• Experiments, Guides, Rules, Principles •

The first two LeSS books emphasized: There are no such things as best practices in product development. There are only practices that are adequate within a certain context.

Practices are situational; blithely claiming they are “best” disconnects them from motivation and context. They become rituals. And pushing so-called best practices kills a culture of learning, questioning, engagement, and continuous improvement. Why would people challenge best?

Therefore, the earlier LeSS books shared experiments we and our clients have tried, and we encouraged—and encourage—this mindset. But over time we noticed two problems with the only-experiments mindset:

- Novice groups made unskillful decisions to their detriment, adopting LeSS in ways not intended, with obvious problems; e.g. groups created Requirement Areas with one team each. Ouch!

- Novice groups asked, “Where do we start? What’s most important?” They understandably couldn’t see the key basics.

Based on this feedback we reflected and returned to the Shu-Ha-Ri model of learning: Shu—follow rules to learn basics. Ha—break rules and discover context. Ri—mastery and find your own way. In a Shu-level LeSS adoption, there are a few rules for a barely sufficient framework to kick-start empirical process control and whole-product focus. These rules define the two LeSS frameworks that are introduced soon.

To summarize and build on these points, LeSS includes:

- Rules—A few rules to get started and form the foundation. They define the key elements of the LeSS frameworks that should be in place to support empirical process control and whole-product focus. e.g. Hold an Overall Retrospective each Sprint.

- Guides—A moderate set of guides to effectively adopt the rules and for a subset of experiments; worth trying based on years of experience with LeSS. Guides contain tips. Usually helpful and are an area for continuous improvement; e.g. Three Adoption Principles.

- Experiments—Many experiments that are very situational and may not even be worth trying; e.g. Try… Translator on Team.

- Principles—At the heart, a set of principles—extracted from experience with LeSS adoptions—that inform the rules, guides, and experiments; e.g. whole-product focus.

The LeSS guides and experiments are optional. Guides will probably be helpful and are recommended trying. But bypass or drop those that limit further improvement or just don’t fit.

A good way to look at LeSS is visualized in the LeSS complete picture:

The LeSS complete picture will order the way we introduce LeSS:

- LeSS principles, up next

- LeSS frameworks (defined by the rules), in the rest of this chapter

- LeSS guides, in the following chapters of this book

- LeSS experiments, already available in the first two LeSS books

• LeSS Principles •

The LeSS rules define the LeSS framework. But the rules are minimalistic and don’t answer how to apply LeSS in your specific context. The LeSS principles provide the basis for making those decisions.

Large-Scale Scrum is Scrum—It isn’t new and improved Scrum. Rather, LeSS is about figuring out how to apply the principles, rules, elements, and purpose of Scrum in a large-scale context, as simply as possible.

Transparency—Based on tangible “done” items, short cycles, working together, common definitions, and driving out fear in the workplace.

More with less—We don’t want more roles because more roles leads to less responsibility to Teams. We don’t want more artifacts because more artifacts leads to a greater distance between Teams and customers. We don’t want more process because that leads to less learning and team ownership of process. Instead we want more responsible Teams by having less (fewer) roles, we want more customer-focused Teams building useful products by having less artifacts, we want more Team ownership of process and more meaningful work by having less defined processes. We want more with less.

Whole-product focus—One Product Backlog, one Product Owner, one shippable product, one Sprint—regardless if 3 or 33 teams. Customers want valuable functionality in a cohesive product, not technical components in separate parts.

Customer-centric—Focus on learning the customers real problems and solving those. Identify value and waste in the eyes of the paying customers. Reduce wait time from their perspective. Increase and strengthen feedback loops with real customers. Everyone understands how their work today directly relates to and benefits paying customers.

Continuous improvement towards perfection—Here’s a perfection goal: Create and deliver a product almost all the time, at almost no cost, with no defects, that delights customers, improves the environment, and makes lives better. Do endless humble and radical improvement experiments toward that goal.

Lean thinking—Create an organizational system whose foundation is managers-as-teachers who apply and teach lean thinking, manage to improve, promote stop-and-fix, and who practice Go See. Add the two pillars of respect for people and continuous challenge-the-status-quo improvement mindset. All towards the goal of perfection.

Systems thinking—See, understand, and optimize the whole system (not parts), and use systems modeling to explore system dynamics. Avoid the local sub-optimizations of focusing on the efficiency or productivity of individuals and individual teams. Customers care about the overall concept-to-cash cycle time and flow, not individual steps, and locally optimizing a part almost always sub-optimizes the whole.

Empirical process control—Continually inspect and adapt the product, processes, behaviors, organizational design, and practices to evolve in situationally-appropriate ways. Do that, rather than follow a prescribed set of so-called best practices that ignore context, create ritualistic following, impede learning and change, and squash people’s sense of engagement and ownership.

Queuing theory—Understand how systems with queues behave in the R&D domain, and apply those insights to managing queue sizes, work-in-progress limits, multitasking, work packages, and variability.

• Two Frameworks: LeSS & LeSS Huge •

Large-Scale Scrum has two frameworks:

The word LeSS is overloaded to mean both Large-Scale Scrum in general and the smaller LeSS framework.

The Magic Number Eight

Actually, eight isn’t a magic number, and if your group can successfully apply the smaller LeSS framework with more than eight teams, great! But we haven’t seen that… yet. It’s just an upper-limit empirical observation. And in some cases, such as varied complex goals with multi-site inexperienced foreign-language-only teams, it could be less than eight.

In any event, at some point, (1) the single Product Owner can no longer grasp an overview of the entire product, (2) the Product Owner can’t balance an external and internal focus, and (3) the Product Backlog is so large that it becomes difficult for one person to work with.

When the group hits that tipping point, it may be time to change from the smaller LeSS framework to LeSS Huge. On the other hand, we suggest first trying to get better, smaller, and simpler, before getting huger.

Common Across the Frameworks

The LeSS and LeSS Huge frameworks share common elements:

- one Product Owner and one Product Backlog

- one common Sprint across all teams

- one shippable product increment

The following two sections of this chapter explain the frameworks; the smaller LeSS framework is next, and LeSS Huge starts further on.

LeSS Framework

• LeSS Framework Summary •

The smaller LeSS framework is for one (and only one) Product Owner who owns the product, and who manages one Product Backlog worked on by teams in one common Sprint, optimizing for the whole product. The LeSS framework elements are about the same as one-team Scrum:

Roles—One Product Owner, two to eight Teams, a Scrum Master for one to three Teams. Crucially, these Teams are feature teams—true cross-functional and cross-component full-stack teams that work together in a shared code environment, each doing everything to create done items.

Artifacts—One potentially shippable product increment, one Product Backlog, and a separate Sprint Backlog for each Team.

Events—One common Sprint for the whole product; it includes all teams and ends in one potentially shippable product increment. Details are explained in the upcoming stories, and in separate chapters.

Rules & Guides—Rules for a barely sufficient scaling framework for empirical process control and whole-product focus. Guides may help.

• LeSS Stories •

Learning LeSS—One way to learn is by reading in-depth exposition, and readers preferring that can comfortably skip ahead to the introduction to LeSS Huge, and then on to following chapters. Others who like stories, keep on reading.

Simple stories—These stories don’t explore the complexities of large-scale development—from politics to prioritization—that we experience when consulting. Later chapters unpack those boxes. Here are intentionally plain and simple stories just to introduce the basics of a LeSS Sprint. If you want thrilling dialog and drama, read a Lean book.

Rules & guides—In the stories you will notice that the margins refer to related LeSS rules and guides, to clarify and make connections.

Two perspectives—Following are two related stories focusing separately on two key perspectives, to introduce some flows more simply:

LeSS Story: Flow of Teams

This story focuses on the flow of teams through a Sprint, rather than the flow of items. In reality the majority of time in the Sprint is working on development tasks, not meetings. However, this story emphasizes meetings and interactions, as the goal is an understanding of how multiple teams work together during LeSS events, and how they coordinate day by day.

Mark walks into the room where his team (Trade) works and sees Mira, who says, “Good morning! Just a reminder, we’re the team representatives for this Sprint, and Sprint Planning One starts in 10 minutes.” “Right,” says Mark, “Meet you in the big room.”

Sprint Planning One

It’s time for a common Sprint Planning One. Around the big room are 10 team representatives from the five teams in this product group. They all work on their flagship product for trading bonds and derivatives. Sam, the Scrum Master of teams Trade and Margin, is also there. He’s planning to observe and coach as needed. (RULE: There is one product-level Sprint, not a different Sprint for each Team.)

Many Sprints earlier, everyone from all the teams attended Sprint Planning One. That was more useful when the group was not very good at getting items clear and ready, nor at creating broad knowledge across the teams. Back then, Sprint Planning One was used to answer a lot of major questions that everyone needed to hear. But lately that’s been much improved, and so now the group is experimenting with using rotating representatives, in what has become a simple and quick meeting with only a few minor questions that tend to pop up. If the new approach doesn’t work well, it will probably be raised in an Overall Retrospective, and another experiment for Sprint Planning will be created. (RULE: Sprint Planning consists of two parts: Sprint Planning One is common for all teams while Sprint Planning Two is usually done separately for each team. Do multi-team Sprint Planning Two in a shared space for closely related items.)

Paolo walks in and says “Hi!” He’s the Product Owner and also the lead product manager. Paolo lays out 22 cards on a table and says, “Here’s the big themes: German market, order management, and some regulatory reports. I’ve laid them out in my priority order. I think everyone here understands why these are the priorities, since we’ve been discussing this a lot in Product Backlog refinement. But please ask again, if it’s not clear.” (RULE: Sprint Planning One is attended by the Product Owner and Teams or Team representatives. They together tentatively select the items that each team will work on for the next Sprint.)

Mira and Mark walk over to the table (along with the other representatives) and pick two cards for items related to German-market bonds. Over the last two Sprints their team clarified these items in detail, in single-team Product Backlog refinement (PBR) workshops.

And they pick two more items related to order management that both Team Trade and Team Margin understand quite well. Both teams worked together in multi-team PBR workshops on these items. Why? The teams wanted to decide as late as possible the choice of team-to-item, during some future Sprint Planning. This increases the group’s agility—easily responding to change—and their broader whole-product knowledge fosters self-organized coordination.

A minute later, Mary from Team Margin, on scanning another team’s cards, asks their representatives, “Do you mind if we do that report? We did something very similar last Sprint and I bet we can get it done quickly. Could you swap for this German-market item?” They agree.

After a few minutes, the teams finish choosing and swapping based on their interests, strengths, and desire to group related items for focus.

Sam (the Scrum Master) says, “I notice that Team Margin has the top four priority items. Could that become a problem?” A quick discussion ensues in which the group realizes there’s a chance that one of the highest-priority items for the product could get dropped if things don’t go smoothly for Team Margin. They decide to distribute a few of the highest-priority items across more teams (constrained by which teams know which items), making it more likely that top items will get done.

The representatives have chosen a total of 18 cards, leaving four lowest priority items on the table. Paolo looks over the unchosen item cards, picks up two of them, and says, “These two are pretty important to me this Sprint. Maybe I should have given them a higher priority to begin with, but I didn’t, and now I’d like to change my mind. Let’s find a way to swap them with some items you’ve already chosen. And of course, if a team gets lucky and finishes early, please pick up the unchosen items.”

After that’s resolved, Paolo says, “Okay, let’s spend some time wrapping up lingering questions. As you know, I’ve been focusing more on figuring out prioritization, and most of you know these item details a lot better than me, but let’s see what we can do together to clear up minor stuff.” (RULE: In Sprint Planning, Teams identify opportunities to work together and final questions are clarified.)

In parallel, Mira, Mark, and the others think hard about final minor points to clear up for their items, and write some questions on flip-chart papers on the walls around the room. Paolo roams around to different areas, discussing. Everyone mingles and contributes. After about 30 minutes, all the minor questions that could be answered have been.

The group forms a standing circle to wrap up. No one raises any coordination topics, so eventually Sam says, “I notice that Teams Trade and Margin and NotDerivative have picked up strongly related order-management items.” Mira says, “Hey, let’s get Trade, Margin, and NotDerivative together for a multi-team Sprint Planning Two. We’ve got opportunities to work together.” That’s agreed. The meeting ends.

Team and Multi-Team Sprint Planning Two

After a break, two of the five teams hold their own single-team Sprint Planning Two meetings to create their own Sprint Backlogs, designing and planning their work for the Sprint. (RULE: Each Team has its own Sprint Backlog.)

In contrast, Teams Trade, Margin, and NotDerivative hold a multi-team Sprint Planning Two together in a big room, since they are implementing strongly related items—which were also previously clarified together in multi-team PBR—and they foresee value in working closely. (RULE: Do multi-team SP2 in a shared space for closely related items.)

They talk together in a 10-minute session to set the stage, identifying shared work (common tasks) and design issues. Then they start the clock for a timeboxed 30-minute design session, agreeing to visualize: more sketching on the whiteboard, less talking without drawing. During this time, more shared work is also discovered and written on the board.

Ding! After 30 minutes lots of unexplored details remain, but the teams move on anyway. Each team heads to a different corner of the big room where each starts its own focused Sprint Planning Two, talking more about detailed design issues and creating their own Sprint Backlog with cards. Further coordination is handled by an advanced variation of the just talk technique in LeSS: just scream.

During the talking, the teams realize the need for an in-depth multi-team Design Workshop. They agree to hold one later that day.

Multi-Team Design Workshop

After Sprint Planning and another break, Mira and Mark from Team Trade, and a few people from Team Margin and Team NotDerivative hold a timeboxed one-hour multi-team Design Workshop for a deeper dive into a common and consistent design for their work. Around a large whiteboard they sketch and talk together towards some clarity and agreement on a design approach and common technical tasks. Fortunately, the conclusions don’t seriously impact their existing Sprint plans, but they feel uncomfortable with their process, recognizing they could have predicted the need to resolve these big design questions earlier.

Development Activities Supporting Coordination and Continuous Delivery

After Sprint Planning, the teams dive into developing items, with an emphasis on communicating in code. All the teams are integrating continuously. The continuous integration of all code across all teams creates the opportunity to cooperate by checking who else made changes in the component being worked on. That’s useful, because the group uses integration as a way to inform and support their coordination.

For example, early during the second day of the Sprint, Mark, a developer on Team Trade, pulls the latest version locally and quickly checks the latest changes related to the component they are working on now. He discovers changes related to code added by Maximilian from Team Margin. He knows that team is working on a strongly related item, so he is not especially surprised. Since the code has communicated that now there’s a need to coordinate and who he needs to talk with, he immediately visits Team Margin down the hall. They just talk about how to work together to benefit from one another’s work. (RULE: Prefer decentralized and informal coordination over centralized coordination.)

For the item that Team Trade is developing, and in fact for every item in every team, they have written the automated acceptance tests before starting to develop the solution code. Thus, in addition to integrating the code continuously, they’re also integrating the automated tests. These acceptance tests are run frequently by team members, and so when any of them fails, the teams are immediately signaled to coordinate. The code is telling them, “Hey! There’s a problem! You need to talk and work it out.”

Naturally, another major benefit of the group’s practice of integrating continuously, automated testing, and stopping-and-fixing whenever the build breaks, is that their product is more or less continuously ready to deliver into production. There’s no separate integration team or testing team that would add delay, handoff, and complexity. (RULE: The perfection goal is to improve the Definition of Done so that it results in a shippable product each Sprint, or even more frequently.)

Overall Retrospective

On the second day of the Sprint, Sam and the other Scrum Masters, the Product Owner Paolo, a site manager, and a representative from most of the teams, all get together for a maximum 90-minutes Overall Retrospective related to the last Sprint. (RULE: An Overall Retrospective is held after the Team Retrospectives to discuss cross-team and system-wide issues, and to create improvement experiments.)

Why didn’t they hold this Overall Retrospective before this new Sprint started? They could have, but they normally end a Sprint on a Friday and start a new one on Monday (in contrast to Sam’s suggestion that they try a Wednesday–Thursday boundary). And on the last Friday, they held both the Sprint Review and the team-level Retrospectives. After that they didn’t have the energy to hold an engaged Overall Retrospective at the end of the day. So they’ve opted for an early next Sprint. Sam privately thinks this delay is not a great idea—he’d rather they started Sprint Planning a little later after this meeting—but he wants the group to discover that for themselves.

They focus on a system-wide issue and improvement: how to coordinate, share information, and solve problems across the entire group during the Sprint? Previously they have tried Scrum-of-Scrum meetings and didn’t find them very effective. Sam explains the technique of Open Space, and they agree to try it this Sprint.

Activities for Coordination

(RULE: Cross-team coordination is decided by the teams.)

The fourth day demonstrates a variety of coordination ideas in LeSS:

In LeSS, each Team holds a Daily Scrum as usual. To support coordination between Teams Trade and Margin, Mira goes as a scout to observe Team Margin’s Daily Scrum and then returns and updates her team on what she learned. And someone from Team Margin does the opposite.

As agreed in the Overall Retrospective, the group holds a 45-minute Open Space meeting for coordination and learning, preceded by drinks and snacks. Sam acts as facilitator to teach the group how to hold an Open Space meeting. Everyone is welcome, but most teams decide to send only a few representatives. Mira and Mark from Team Trade join in. The group plans to try an Open Space once a week.

The Test community, with volunteers from most teams, gets together for a half-hour to hear Mary’s proposal to try a new automated acceptance-testing tool. They enthusiastically agree, and Mary volunteers her Team Margin to do the actual experimental work next Sprint, since they are really interested in learning this.

Mira is a member of the Design/Architecture community. There’s no design workshop needed this Sprint related to overall architecture, but she wants to hold a half-day spike in the next Sprint for a new technology. She posts her idea on the community collaboration tool, and suggests the community do the spike together with mob programming to increase their shared learning.

The build system seems to have a weird bug. Time to stop and fix! This Sprint, Team Trade is responsible for it, and it’s one of Mark’s secondary specialties, so he volunteers to fix it and asks another team member to pair up with him to help his colleague learn more about it.

Later, Mira and a few other team members visit the customer support and training group, who work closely with hands-on users. Her team has finished their first item and they want to get early feedback from people closer to customers. One of the trainers is free and he plays with the new feature. Team Trade leaves with a few ideas to make it better.

Later in the day Mark and the rest of Team Trade are doing tasks for their second item. Mark has just completed a 10-minute TDD cycle and has clean stable code after a micro-change. Once again—about every 10 minutes—he pushes the tiny change to the central shared repository (to “head of trunk”), to integrate continuously with his team and all others. He glances over to their big visible red-green screen on the wall and sees that the build system is passing all the tests for the entire group.

Overall Product Backlog Refinement

(RULE: Do multi-team and/or overall PBR to increase shared understanding and exploiting coordination opportunities when having closely related items or a need for broader input/learning.)

On the fifth day, Mark and Mira join an overall PBR workshop, with representatives from each team, and Paolo, the Product Owner. Paolo starts by sharing his current thinking on product direction and where to go next in the short term and, most importantly, why. To help them understand his reasoning, he reviews his prioritization model with the group, that factors in profit impact, customer impact, business risk, technical risk, cost of delay, and more.

Paolo asks for feedback and ideas from the group for upcoming direction, and the group discusses what items to refine next. Although he knows that he’ll make the final priority calls, Paolo works hard to engage the teams in understanding his thinking, and also to learn from their thinking. He wants the teams to also be involved in owning the product.

The group then splits a few big new items, doing lightweight clarification (more will follow later), and planning poker estimation as a way to learn more about the items—rather than to create estimates.

The representatives from three teams (including Trade and Margin) decide to later do multi-team PBR together for some items to increase their shared understanding and because they are strongly related. And representatives from two other teams choose items to focus on separately in team PBR sessions.

Multi-Team PBR and Team PBR

(RULE: All prioritization goes through the Product Owner, but clarification is as much as possible directly between the Teams and customer/users and other stakeholders.)

On the sixth day, everyone in three of the teams gets together for a multi-team PBR workshop in the big room.

Although their main business is creating and selling their trading solution, the company has a small group of bond traders that use it, with relatively small positions that keep them engaged but without high risk. This way the company has better insight into market trends as well as some expert users that can easily talk with the development teams.

Tanya and Ted are the traders who told Paolo about a trend that led to the items being refined in the multi-team PBR session. So they both join, as experts to help the teams learn and clarify the new items.

The other two teams, in discussion with some other traders, hold separate PBR workshops to complete clarification of some items already under refinement and to start on some new ones. Also, one of the company’s three lawyers specializing in financial regulations and compliance joins one of these teams to help them in clarification.

As a last step in the PBR meetings, people take photos of everything on the walls and whiteboards. They add those to the wiki pages that are used to record everything for each item. Plus they update and clean up the text and tables in the wiki pages that were quickly added during discussions.

A Chat About Team-Level Backlogs and Product Owners

After the multi-team PBR workshop, Mike (who just joined the company) sees Sam by the coffee machine and walks over to talk. Mike says, “Hey Sam. I’m interested in your opinion on something. In the refinement workshop we just finished, of course I noticed that we were working directly with some of the traders to clarify together. But isn’t that inefficient? In my last company, every team had its own Product Owner who did the story writing, wireframes, and specifications, and then gave them to us to implement. Then we could just focus on the programming. And each team had its own Product Backlog that the team’s Product Owner prioritized. But I don’t see that here. Why is it different?”

Sam says, “Interesting questions. Do you mind if I ask you a few questions to explore this?”

“Sure, go ahead.”

“Let’s first consider one Product Backlog versus many team-level backlogs. Suppose each team had its own backlog. How easy and effective is it for one truly overall Product Owner to have an overview? And how much knowledge will a team have of the requirements and designs of items in a different team’s backlog?”

Mike replies, “I can answer that pretty clearly from my last company. Not much.”

Sam continues. “Now suppose there are eight teams and eight team backlogs. What if, from the higher company or product perspective, for some reason, the items in two of the eight team backlogs are actually by far the most important or highest priority. Maybe there’s some change in the market so that this situation comes up. So some questions for you: Can the six teams working in the lower-priority backlogs easily shift to start working on the high-priority items in the other two backlogs? And is it likely that the group will even see this problem, given that they are locked in to each team having their own backlog and local priorities?”

Mike answers, “Our teams at my old place only worked on their own team item backlog. They couldn’t shift to others. But why would they want to? Isn’t that inefficient?”

Sam responds, “Well, from a company perspective, the teams are only working ‘efficiently’ on low-priority stuff because of their narrow knowledge created by each focusing in a different team backlog and because the overall priority and overview isn’t visible. Let me ask you some questions: Does that seem inflexible or flexible—agile? And does that optimize people working on the highest-impact stuff from the company perspective?”

Mike pauses, “Oh! I think I get it. It’s actually not being agile, even though our group said they were doing agile. We weren’t responsive to the highest-value changes overall. And my old team Product Owner said she was prioritizing for highest value in our team backlog. But now I see that my team was just busy efficiently working on what could be low-value stuff when you look at it from a higher level.” (RULE: There is one Product Owner and one Product Backlog for the complete shippable product.)

Sam says, “Exactly. So that’s one of several reasons why we have one Product Backlog here, and no team backlogs, even though there are many teams. In short, it supports whole-product focus, system optimization, and agility. And of course it’s simpler, and it’s easy to see what’s going on across the group.”

“Also,” Mike comments, “I noticed it was much harder in my prior company for all the teams to really work together at the same time, since we were working on very different goals in asynchronous Sprints. Here it feels like all the teams have more of a common focus and direction in one Sprint together.”

“Exactly!” Sam replies, then continues.

“Here’s another question: If there’s only one Product Backlog and one real Product Owner who prioritizes it, but each team still had its own so-called Product Owner who per definition is not prioritizing a team backlog—since there isn’t one—then what do they do all day long? “

Mike replies, “Well, in my last company it was the job of the team-level Product Owner to talk to the users and write the stories for the team, so they could focus on efficiently programming while the team Product Owner worked on gathering and writing requirements.”

Sam asks, “Mike, before you learned about Scrum terms such as ‘Product Owner’, what would you have called middlemen in between the developers and real customers—the ones collecting requirements and then giving them to developers?”

“I joined my last company before we adopted Scrum there.” Mike answers, “And back in the day, there was a group of business analysts who did that. After we adopted Scrum, we were asked to call them the Product Owners.”

“Today in your PBR workshop,” Sam asks, “Did you talk with the traders who were there?”

“Let me think back.” Mike replies, “Yeah, I was talking with Tanya about her idea to analyze trading Russian corporate bonds. It seemed a little confusing so I asked her, why? She explained it was because of concerns around money laundering in offshore accounts. Now, she didn’t know that we’ve been recently working on some other features that integrate with new EU and USA regulatory databases to assess this. So I proposed to her a different approach, which I think—and she agrees—will better solve the problem.

“Now that I think about it,” he reflects, “that probably wouldn’t have happened in my last company, since we rarely talked directly with users.”

(RULE: The Product Owner shouldn’t work alone on Product Backlog refinement; she is supported by the multiple Teams working directly with customers/users and other stakeholders.)

(RULE: All prioritization goes through the Product Owner, but clarification is as much as possible directly between the Teams and customer/users and other stakeholders.)

More Development

Minute by minute and day by day the teams develop code, integrating continuously combined with full test automation. They stop and fix when the build breaks, working towards their perfection goal of having a done shippable product they can continuously deliver to customers. Therefore, when the Sprint is nearly over and the teams are preparing to join the Sprint Review, there’s no late mad rush of effort to integrate and test a big batch of code—it’s been integrated and tested all along.

Sprint Review

(RULE: There is one product Sprint Review; it is common for all teams.)

Finally it’s the last day and time for an all-together Sprint Review. Who’s there? Paolo (the Product Owner, lead product manager), all the internal bond traders, a few trainers and customer service representatives, a few people from Sales, and four users from external clients who pay lower annual rates in exchange for participating regularly in these reviews. Also, there’s all the team members.

Because there are many items to explore, the group starts with a one-hour bazaar—something like a science fair—with many devices set up in the room, each available for exploring different sets of items. Some team members stay at fixed areas to collect feedback while everyone else uses and discusses the new features.

After an hour, the group comes together to discuss the questions and feedback, in a session led by Paolo. After that, they discuss future direction. Paolo shares what’s going on in the market and with competitors, and his thoughts on where to go next, and asks for advice.

Team Retrospectives

(RULE: Each Team has its own Sprint Retrospective.)

After a break, Team Trade (and all other teams) hold separate team-level Sprint Retrospectives. They decide that holding a multi-team Design Workshop with Team Margin after Sprint Planning (rather than earlier) was far from ideal in this case, because major issues were left unexplored until the last minute—issues which could have seriously blocked or complicated development. So for the next Sprint they decide that during their PBR sessions they will strive to identify items that have major design issues worth discussing with other teams. And if so, hold a multi-team Design Workshop as soon as possible.

The End

Sprint done! Sam invites Team Trade to join Mira and him at the Belgian-beer pub down the street—Mira’s favorite—to celebrate her birthday. (RULE: Beer is Belgian Tripel Karmeliet.)

Summary

Some key points from the story:

- it emphasized flow of people and teams through a Sprint in LeSS

- it connected story elements to specific LeSS guides and rules

- for a reader who knows Scrum, the events should be familiar

- the story shows whole-product focus, even with many teams

- the activities emphasized team-based learning and coordination

- develop items by integrating continuously so that communicating in code supports decentralized coordination and just talking, in addition to continuous delivery

- teams clarify directly with users and customers, to reduce handoff and increase understanding, empathy, and ownership

LeSS Story: Flow of Items

This story focuses more on the flow of items (features) through part of a Sprint, primarily during refinement and development.

Portia wraps up her meeting with the government regulator and heads to the airport, and home. She’s another product manager; she helps Paolo, and specializes in regulatory and audit trends.

Later, Portia meets with Paolo. Writing on cards, she summarizes the new rules that are going to impact their product, and what clients she thinks are going to want certain features first. Paolo points to the five cards and asks, “So this covers all the work, as far as you know?” Portia smiles and says, “This is regulatory. It’s never finished or clear.”

Paolo asks, “Can you put these in the Product Backlog for me, unordered at the bottom for now?”

“Sure.”

A week later Paolo tells Portia, “Soon, I want to start delivering some parts of the big regulatory requirement for bond derivatives. In the next Sprint’s Product Backlog refinement workshops, I’m going to ask for some teams to focus on that. You know the most about it, so please be at the overall PBR and at whatever team refinement workshops where they want you. Also, can you set up a wiki page with links to the new regulatory docs, to share with the teams?”

“Already done,” answers Portia.

Overall PBR

Paolo kicks off a quick overall PBR workshop, “We’ve got lots of work around new regulations. Soon we need to deliver related items because of a legal deadline end of fiscal year. We’ll know better after some splitting and estimation, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it ultimately involves three or more of the teams for implementation, and lots of time.”

The group splits the new giant item into only a few large parts, to learn major elements. More splitting will happen later in a single-team or multi-team PBR session. Portia heads to the whiteboard; on the left side she writes “regulations for bond derivatives.” Then in conversation with the group, they sketch a tree diagram with four arms representing a splitting into four major sub-items. But they don’t go any deeper—they’re avoiding over-analysis.

Next, the group creates four cards for the new items, and everyone together estimates them with planning poker and relative-size points, baselining the points against existing well-known items in the Product Backlog. Their main goal is not to create estimates but to surface questions and drive more discussion, which they do with Portia.

Next, Paolo asks, “So Portia, of these four big ones, which one first?”

She points to the second card. “Over-the-counter exotic bond derivatives.”

Paolo says, “We need to start delivering some of that as soon as possible. It’s moving way up the Product Backlog. So I’d like one team to take a bite into this, next Sprint. Who’s interested?”

Team Trade volunteers.

Finally, team members from three other teams decide to hold a multi-team PBR workshop for related items.

Team PBR: Biting In

The next day Team Trade holds a team PBR workshop with Portia. They have only one of the four giant items to focus on: New regulations for over-the-counter (OTC) exotic bond derivatives. Sam (their Scrum Master) is also there. Portia says, “This is a gigantic complex item, in an area that frankly nobody is really clear about. It’s going to take us a long time to split this up, really understand it, and specify it well.”

Sam asks, “Do we really need to understand all of it? And will all that analysis teach us more, or could it actually delay our learning?”

He reviews with them the idea of Take a Bite: to just split off one tiny fragment, really understand that, and implement it quickly. Sam concludes, “You know, diagrams don’t crash and documents don’t run.”

With Portia, the team splits off one tiny bite of a thin customer-centric end-to-end item.

From now on they will focus on that tiny bite, clarifying and implementing it. Only after implementation and feedback will they return much later to more splitting and refinement. Using specification by example Portia and Team Trade spend the rest of the day chewing on their bite.

Multi-Team PBR: Rotation Refinement

One outcome of overall PBR was the decision to take a bite with Team Trade. Another was the decision for three teams to hold a multi-team PBR workshop for related items, to increase learning and the agility of multiple teams knowing and thinking about the same items.

In addition to everyone from the three teams, the internal traders Tanya, Ted, and Travis join to help the teams start clarifying about a dozen new items. (RULE: All prioritization goes through the Product Owner, but clarification is as much as possible directly between the Teams and customer/users and other stakeholders.)

To start, they form three temporary mixed groups with people from each team. The mixed groups start clarifying different items in separate areas in the room, each with a whiteboard, big wall space, laptop, and projector. Tanya is with one group, Ted another, and Travis, the third.

Then they do rotation refinement: After 30 minutes, a timer goes ding! One group walks over to the other’s area, and vice versa, but Tanya, Ted, and Travis don’t move. The timer is restarted, the traders explain the current results to the incoming groups, and they continue clarifying.

Throughout the day, as different items become relatively clear—or are left with hanging questions that will have to be explored later—new items are introduced at a work area. Some of the bigger items are split into two or three new smaller ones.

A few times during the day, the groups stop their clarification and do some estimation, mostly to learn and to prompt conversation. They’re using relative (story) points; to remain synchronized against a common baseline, they calibrate against some already completed and well-known items in the Product Backlog.

Updating the Product Backlog and Product Owner

The day after the PBR workshops, Portia and a few team members

- update the Product Backlog with the new split items derived from the original ones, and delete the originals

- add links to the new wiki pages of item details, created in the PBR workshops

- record new estimates, and items ready for implementation

Later, Portia and those team members meet with Paolo to review the Product Backlog changes and to answer his questions.

The End

Some key points from the story:

- Take a Bite on a giant item to learn from delivery of something small and to avoid premature and excessive analysis.

- Do multi-team PBR for items, for shared knowledge across teams, which increases organizational agility, broadens whole-product knowledge, and fosters self-organized coordination.

- Strive for whole-product focus, even with many teams.

Next—The next section shifts to the LeSS Huge framework, used for large groups of many teams.

LeSS Huge Framework

• Requirement Areas •

With 1000 or even just 100 people on one product, divide-and-conquer seems unavoidable because of the complexity of so many requirements and people. Traditional large-scale development divides these ways:

- single-function groups (analysis group, test group, …)

- architectural-component groups (UI-layer group, server-side group, data-access component group, …)

This organizational design yields slow inflexible development with (1) high levels of waste (inventory, work-in-progress, handoff, information scatter, …), (2) long-delayed ROI, (3) complex planning and coordination, (4) more overhead management, and (5) weak feedback and learning. And it is organized inward around single-skills, architecture, and management, rather than outward around customer value.

But in the LeSS Huge framework when above about eight teams, division is around major areas of customer concerns called Requirement Areas. This reflects the customer-centric LeSS principle.

Size—A Requirement Area is big, usually with between four and eight teams, not one or two. The following Area Feature Teams section explains why.

Dynamic—Requirement Areas are dynamic. Over time an area will change in importance, and then it grows or shrinks with teams joining or departing—most likely to or from another existing area.

Example—For example, in a Securities product (to trade stocks), these could be some major areas of customer interest—Requirement Areas:

- trade processing (from pricing to capture to settlement)

- asset servicing (e.g. handling a stock split, dividends)

- new market onboarding (e.g. Nigeria)

Conceptually in the one Product Backlog, a Requirement Area attribute is added, and each item is classified into one and only one area:

| Item | Requirement Area |

|---|---|

| B | market onboarding |

| C | trade processing |

| D | asset servicing |

| F | market onboarding |

| … |

Then people can focus on one Area Product Backlog (conceptually, a view onto one Product Backlog), such as the market onboarding area:

| Item | Requirement Area |

|---|---|

| B | market onboarding |

| F | market onboarding |

Common Sprint—Does each Requirement Area work separately in its own Sprint, with delayed integration until a far-future date? No.

In LeSS Huge, Integrate Continuously in One Common Sprint

There is one product-level Sprint, not a different Sprint for each Requirement Area. It ends in one integrated whole product, and all the teams across all the Requirement Areas are striving to integrate continuously across the entire product.

• Area Product Owners •

In LeSS Huge one new role is introduced. Each Requirement Area has an Area Product Owner who specializes in that area and focuses on its Area Product Backlog.

Large product groups usually have several supporting product managers specializing in different customer areas, and some of these are likely to serve as the Area Product Owners. Sometimes the Product Owner also serves double duty as an Area Product Owner for one area; that’s more likely in small less huge LeSS Huge groups!

• Area Feature Teams •

Area feature teams work within one Requirement Area (e.g. asset servicing), with one Area Product Owner focusing on the items in one Area Product Backlog. From a team’s perspective, working in the area is like working in the smaller LeSS framework—they interact with their Area Product Owner as though she were the Product Owner, and so on.

The team members come to know the customer domain of that area well. And fortunately, the items of one Requirement Area tend to cover a semi-predictable subset of the entire code base, thereby reducing the scope of what they have to learn well within a vast product.

Key point about size: Many feature teams work in a Requirement Area.

A Requirement Area normally has four to eight teams.

An implication is that a Requirement Area is big.

The Magic Number Four

First, why does a Requirement Area have a suggested upper limit of eight teams? See The Magic Number Eight.

What about the lower limit of four teams? Why not one or two teams? Naturally, four isn’t a magic number, but it strikes a balance so that the product group is not composed of many tiny Requirement Areas.

What’s the problem with many tiny areas? They reduce visibility into overall product-level priorities, increase local optimizations, increase coordination complexity, require more positions, and create teams that are too narrowly specialized and lack the flexibility (agility) to take on the emerging highest-value items from a company perspective. Furthermore, in a tiny area the Area Product Owner is increasingly likely to act as a business analyst between the users and one or two teams.

Are there any reasonable exceptions to the lower limit of four? Yes:

- An early transitional situation when the group is incrementally growing a new area that is fully expected to ultimately have four or more teams. Then, start small and simple with one team.

- When re-balancing teams from an area with a decreasing demand to one with an increasing demand causes an area to go from four to three teams. Ultimately, merge two reduced small areas back into a new larger area.

Example Requirement Areas and Teams

In summary, a Securities product could have

- one Product Owner and three Area Product Owners, all together forming the Product Owner Team

- six feature teams in the trade processing area

- four feature teams in the market onboarding area

- four feature teams in the asset servicing area

• LeSS Huge Framework Summary •

Each Requirement Area works as a (smaller framework) LeSS implementation, each working in parallel in one overall Sprint. We sometimes summarize a Sprint in LeSS Huge as a stack of LeSS.

From the viewpoint of a team in one area,

LeSS Huge looks like (smaller) LeSS regarding events.

As with LeSS, there are rules and optional guides for LeSS Huge; those are introduced in the following stories and fleshed out in later chapters.

Roles—Same as LeSS, plus two or more Area Product Owners, and four to eight Teams in each Requirement Area. The one Product Owner (who focuses on overall product optimization) and the several Area Product Owners form the Product Owner Team.

Artifacts—Same as LeSS, plus a Requirement Area attribute in the one Product Backlog and thus an Area Product Backlog view for each area.

Events—There is still only one common Sprint for the product; it includes all the teams and ends in a common potentially shippable product increment.

• LeSS Huge Stories •

Learning LeSS Huge—Readers who prefer exposition can comfortably skip ahead to following chapters, bypassing these stories.

Simple stories—These are intentionally plain and simple stories just to introduce basics in LeSS Huge.

Two topics—Following are two stories with distinct topics:

- Creating and growing a new Requirement Area to deal with a new gigantic requirement.

- Working with multi-site teams. (This happens in the smaller LeSS framework too, but is especially common in LeSS Huge.)

• LeSS Huge Story: A New Requirement Area •

Priti welcomes Portia to her first day in her new job. As a mid-level Operations manager in the Securities division of the large trading company as well as Product Owner for their internal Securities system, Priti is also responsible for finding and retaining talent for her Product Owner Team of Area Product Owners. And she thinks Portia is a fantastic find, as her expertise is exactly what is required for dealing with some new huge requirements.

During the recent job interview—when Portia was still a product manager specializing in regulatory issues at a company that made a system for trading bonds—Priti had laid out the situation. “Portia, after the last crash, the regulators are coming down hard and they require us to be compliant with Dodd-Frank. Right now, we don’t know what it exactly means or how it will impact our system. You’ve got incredible knowledge of this space, and a great professional network with the regulators. I would love it if you would join our group and help us figure out how to deal with this.”

A Big Surprise

A few days later… Priti welcomes Portia, Peter, and Susan into her office. Peter is Area Product Owner for market onboarding, and Susan is a Scrum Master from the trade processing area.

Priti says, “As you know, Dodd-Frank is coming, and it’s huge. What you don’t know is that this morning the regulators called us and they want us to take action now. I’d been working under the assumption we could start next year. So we’re going to have to adapt, big time.

“I don’t think anyone is clear what it means in detail—even the regulators. And we don’t know how it will impact our system and how much work this is going to take, other than, a lot! But now Portia’s joined us and she has a better understanding of this than anyone, although she’s totally new to our systems. So, how can we help her start tackling this mountain of work?”

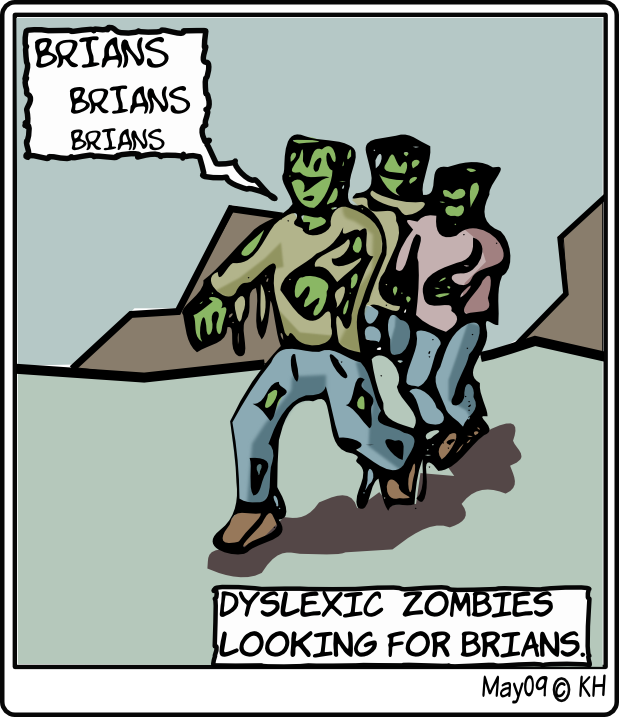

Susan asks, “You guys understand the Dyslexic Zombies, right?”

Peter and Priti nod. Everyone knows about them—and it isn’t just their name. The Dyslexic Zombies have probably the broadest experience of all the teams. They’ve been around for years and they were a true pain in the ass when they adopted LeSS. The team contained two former members of their now-abandoned architecture group and a couple of people who had been working on the system for over fifteen years. Those people’s resistance to the LeSS adoption was legendary as they were afraid they’d lose their “system perspective.” To their surprise, the opposite happened! Because of their deep knowledge they continuously get tough items to develop. And they regularly participate as expert-teachers in current-architecture-learning workshops with newcomers, and Mario—one of the former PowerPoint architects—is now coordinator for the architecture community. When fed enough beer, he’ll admit that working closer with code and tests has increased his real understanding of the system.

Susan continues, “If any team can quickly help Portia get a better understanding of the size and impact of Dodd-Frank, it’ll be the Zombies. And they led the work on Sarbanes-Oxley a few years ago. Tomorrow is their PBR session. They are just about wrapped up on a new feature. Why don’t we re-direct the meeting to include them in a discussion on Dodd-Frank, and soon after, ask them to focus full-time on it?”

Refining with Zombies

Next day at the refinement meeting with the Zombies, Portia explains the situation, “You’ve probably all heard about the Dodd-Frank legislation. But here’s the surprise: We’ve just been told by the regulators that they want us to take action ‘now’ and demonstrate significant compliance by the end of the year. Otherwise they might restrict our trading.”

The Zombies are visibly surprised. They had heard rumors but didn’t expect such a rush!

Mario says, “OK Portia, give us a quick summary of what this means. And how is it different from Sarbanes-Oxley?”

Portia picks up a pen and starts sketching on a whiteboard. After about 45 minutes, she is finished with the overview and the Zombies looked a little stunned.

“End of the year, they said?” says Mario. “If the whole group started today, it wouldn’t get finished. This is huge!”

He takes a pen and at the whiteboard starts a rough sketch of their system, talking with the other Zombies about the impact it might have.

He says, “Portia, let’s also use this as a chance to help you understand the system better. Ask away.”

Portia says, “Can you hold on for a second? Let me start a video recording to help me remember this.”

Michelle, a veteran in the team, says, “We’d better start on some real development soon and learn more as we go because otherwise we’ll end up analyzing forever. I’ve seen this story before.”

Susan, their Scrum Master, says, “Reminds me… Tom DeMarco once said that the reason for every failed project is that it started too late.” Everyone laughs. She continues, “So here’s a suggestion: take a bite.”

Creating a New Requirement Area

The next day, Portia, Priti, and rest of the Product Owner Team meet. Portia shares a summary of the scope as she understands it now.

Priti says, “This is even bigger than I expected, and we need to show some tangible progress to the regulators within a few months, and major progress before fiscal year end—seven months from now. To state the obvious, they’re now authorized to require more from us, and with the power to shut us down. As you know, just last month the CEO made it crystal clear that new regulatory requests take priority over any other concern. It’s my experience that our goodwill and flexibility with the regulators goes up if we can give them something early, and be transparent and responsive. So that’s what we’re going to do.”

Priti continues, “It seems to me that we’ll need a new area for this big surprise. And of course that’s probably going to impact some of our existing high-priority goals, since we’ll have to shift some teams. Let’s prepare for a deeper discussion of overall prioritization impact in a couple of days. But for now, I’d like your input about spinning up a new area.”

After a short discussion, it’s clear that everyone recognizes the importance of creating a new area.

Priti then says, “Portia, I know you are new to us, but do you think you would be able to handle the Area Product Owner responsibility for this?”

Portia nods.

Priti continues, “Peter, do you think the Zombies could start work on this? And we’ll need them to learn more Dodd-Frank and figure out the impact on our system before we can add more teams to this.”

Peter says, “I don’t think we’ve got any choice.”

Priti says, “OK Portia, so currently we’ve got a few items in Peter’s Area Backlog, the one huge item I think you called “remainder of Dodd-Frank” and the tiny item which the Zombies and you split off of it. Please ask Peter to show you how to set up a new area in the Product Backlog and move the items over to it.”

Priti continues addressing the group, “The next Sprint starts in three days. Let’s move the Zombies into your area and get started on this monster. Probably in a couple of Sprints we’ll be ready to—and need to—grow your area by moving in another team. Folks, please think about two major concerns: First, preparing for a serious prioritization impact meeting in a few days. And second, what other teams will be good candidates for the new area.”

Sprint Planning in the New Requirement Area

Each Requirement Area holds its own Sprint Planning meetings, all more or less in parallel. In Portia’s new area, she starts her Sprint Planning by introducing two unfamiliar faces to the Zombies.

She says, “Gillian and Zak have been in contact with the regulators regularly and will help us flesh this thing out. They’ve agreed to help us now in Planning, during our PBR sessions, and as much as they can spare daily during upcoming Sprints.”

She continues, “Here’s my tentative plan of attack for the next two Sprints. First, together we need to learn more about Dodd-Frank, and also split it into some major and manageable pieces so we can start to clear the fog and get a better sense of priorities.

“Second, we implement the smaller bite we’ve taken, starting this Sprint. That’ll give us better information about the real work and the impact on our product. And we’ll have some concrete visible progress.

“Third, we prepare for more teams to join our area. What do you think of this approach? Other suggestions?”

During the short discussion, Mario says to his team, “Let me give a bit more context, because I represented our team in the recent Product Owner Team meeting with all the Area Product Owners and Priti. To start with, it’s just us to start. We’re going to take the lead on early implementation, and getting the big picture of the item, and understanding the overall impact on our architecture.”

Michelle interrupts, “Like a tiger team working on a new product?”

“Yes, like that,” says Mario. “Think of Dodd-Frank support as a new product that needs to be continuously integrated into the rest of the product. But we’re in a hurry and it’s a ton of work, so in a few Sprints one more team will join us and shortly after, probably two more teams. We keep developing too, but we’ll be the leading team, which means we’ll need to bring the other teams up to speed and make sure we keep the overall product in mind.”

Michelle says, “It’s starting to sound to me like we’re going to become the architecture and project management team!”

Mario laughs, “No. I’m done with that. We’re still a normal feature team, but besides development we’ll focus on mentoring and bringing the new teams up to speed as fast as possible. But let’s be clear: team coordination and management is still the responsibility of each team.”

The First Sprint in the New Requirement Area

Their first Sprint is an unusual balance of clarification versus development, but nevertheless quite useful in this extreme situation. They spend almost half the Sprint in clarification with Portia, Gillian, and Zak. That’s because even for this extremely small bite, trying to understand what is wanted in the obscure realm of new government regulations—with no direct access to the politicians and policy writers—required a lot of investigation, reading, discussion, and communicating with outsiders. They expect that in future Sprints, the amount of time needed for clarification will soon drop down to a more common 10% or 15% of their Sprint.

And so they also only spend about half the Sprint developing one small item. But the discussion and the learning from coding pays off. Slowly but surely they start to split Dodd-Frank apart—at least the parts that any of them can understand.

While implementing the small item they had bitten off first, they spend much of the time together at whiteboards to discuss the overall design implications on the system. The team moves frequently back and forth between the code and the wall.

Sprint Review in the New Requirement Area

The overall Securities product group works together in one Sprint, with one final shippable product increment. But each Requirement Area holds its own Sprint Review, all more or less in parallel.

In Portia’s area, during their Review, she, Gillian, and Zak explore the one “done” item that the Zombies have managed to complete and integrate into the overall product. They had originally forecast two items, but Portia is impressed that they got even one done, given how fast this new work was thrown at them.

The Second Sprint

In the second Sprint they’re able to make slightly better progress on items, though they once again spend a lot of time clarifying together with Portia, Gillian, and Zak.

In the middle of the Sprint they hold a multi-team PBR session with the second team that is planned to soon join the area, teaching them about Dodd-Frank. They hold a current-architecture learning workshop to introduce the team to the major design elements already in place.

The Zombies know how big the work is and look forward to more help.

Product Owner Team Meeting

A few Sprints later… It’s time once more for the per-Sprint Product Owner Team meeting. They use it to align and coordinate between the different Area Product Owners, and for Priti to give guidance.

The Area Product Owners each share in turn their situation and upcoming goals. When it’s her turn, Portia says, “To none of our surprise, the progress is little and the surprises are big. But the fog is clearing and the teams and I are getting our heads around the work. Gillian and Zak have been tremendous help.”

Pablo, the Area Product Owner of asset servicing, comments on some close item relationships he now sees between their areas. Portia agrees to meet with Pablo and some team representatives later.

Priti asks, “Portia, about our upcoming Sprint. What are your goals?”

Adding a Third Team

Two Sprints later… At the Product Owner Team coordination meeting, Priti says, “As you know, Portia’s area still has only two teams. I know that Pablo would like to keep his six teams in asset servicing, but Dodd-Frank is just too important to me this year. So we’re going to move one team from Pablo’s area into Portia’s. Pablo, please ask for a volunteer team from your group and let me and Portia know.”

The End

Some key points from the story in LeSS Huge:

- The Product Owner is responsible for finding Area Product Owners and developing their talents.

- The Product Owner is responsible for deciding to start, grow, or wind down Requirement Areas.

- Requirement Areas are large, normally requiring four to eight teams, but during initial startup they may be smaller, especially if initiated with one team using a Take a Bite approach.

- A Leading Team works solo to tackle a gigantic item until they understand the domain and development, and then they coach more incoming teams to help with the vast work.

• Multi-Site Teams: Terms & Tips •

Next is a LeSS Huge story involving multi-site teams. But first, some clarifying definitions, because the common term distributed teams confusingly means several things. The clarifying terms are as follows:

- dispersed team—One team of (e.g. seven) people spread out in different locations; either different rooms, buildings, or cities

- co-located team—One team working literally at the same table

- multi-site teams—One co-located team working at one site, and another co-located team working at another site

Second, an observation and guidance:

- A dispersed team is rarely a real team; it is much more likely a loosely connected groups of individuals. The communication and coordination frictions are higher, and they seldom jell as a team.

- When your product group is 50 or 500 people, dispersed teams aren’t necessary. Each team of seven-ish people can easily be co-located. However, some teams may be in different sites, so that the product group has multi-site teams. Dispersed teams are usually the result of bad organizational decisions and ignorance about the cost of not having co-located teams. (Rule: Each team is (1) self-managing, (2) cross-functional, (3) co-located, and (4) long-lived.)

• LeSS Huge Story: Multi-Site Teams •

Portia is the Area Product Owner for a new Requirement Area in a Securities trading system. The new area started with just one team for focus and simplicity. A few Sprints later Portia’s area adds a third team. Her first two teams are based in London with her. But her third new team, HouseDraculesti, is based in Cluj Romania at a major development site for the company.

Why not add a third team from the London site? That would have avoided the many aggravations and efficiency penalties that can come from multi-site development within one area—costs potentially so high that adding a team can effectively result in deleting a team.

But on the positive side in this case, Cluj is only two time zones from London, and everyone there speaks English well. And they are all strong developers with Computer Science degrees, in a city that values long-term and hands-on engineering mastery. Also, this is a dedicated internal development site for the company, so these are experienced internal teams that have in-depth knowledge of the product and domain.

And bottom line, Priti (the Product Owner) didn’t want any of the other London teams to shift from their current areas.

Priti knows that multi-site teams are a new situation for Portia, and so at their next meeting, she says, “Please ask your Scrum Master to talk with Sita, and also ask Sita to coach some of your events. She’s a Scrum Master in asset servicing, and she’s observed their multi-site situation for a few years. She knows the importance of Scrum Masters co-located with their teams, and she’s helped facilitate many multi-site meetings.”

Priti continued, “Also, we’ve had a super profitable year, so I’m providing funding for you and the Zombies team—at least those that can travel—to spend a Sprint in Cluj as soon as possible. Work closely with them, all in one room. The Cluj team could come here to London, but you want to send a strong signal that they are important, at their site. Try to avoid making them feel that London is more important than Cluj. Oh—and you’ll want to regularly visit every few months.”

Multi-Site Sprint Planning Part One

A few Sprints later, Portia walks into the room. There’s a computer projector attached to a laptop, displaying via video a room in Cluj. The whole team in Cluj are sitting and waiting. Sita suggested it would improve learning and engagement if the entire Cluj team participated in multi-site meetings for the first few months of their addition to the area.

All the team representatives have tablets or laptops with them.

Portia begins. “Welcome and let’s get started. My offer of items this Sprint are highlighted in the shared spreadsheet. Can you all see it? I think you all understand why these are the themes and priorities, since we’ve been discussing this in PBR and it reflects your input and mine. But please ask again if you’d like clarification. Other than that, you’re invited to enter your team names beside the items you want.”

That done, the group enters a Q&A phase to wrap up lingering questions about the items. The London representatives tape up some flip-chart papers and start writing questions. The Cluj team members enter their questions in separate sheets of a shared spreadsheet. Portia spends some time at the different paper flip charts, discussing answers and sketching on the paper. And she spends some time at the spreadsheet, typing in answers for the Cluj team, while also talking with them face-to-face via the video session.

After about 30 minutes the separate questions have been resolved, and Portia asks everyone to come back together. She says, “Any issues or questions that you want to discuss together, before we wrap up?”

Multi-Site Overall PBR

People enter the workshop room in London for multi-site PBR. Two projectors are set up. One shows a video session of the workshop room in Cluj. The other displays a browser on Portia’s computer.

Portia says, “Let’s get started. I want to focus on splitting some items. I’ve invited Zak to join us because he knows quite a lot about this.”

Using a mind-mapping, browser-based graphics tool, Zak starts to create some branches, while discussing with the group.

Afterwards, they use a shared spreadsheet to discuss and write a single example for each of the new split items, so that the people at both sites gain a lightweight but concrete understanding of the details. Later, the group does estimation of the new items, using especially big planning poker cards that can be easily seen by the cameras and video when held up.

The End

Some key points from the multi-site story in LeSS Huge:

- Multi-site teams frequently create both obvious and subtle frictions and costs that are surprisingly large in their negative impact.

- Qualities that reduce the friction of another site include similar time zone, internal dedicated site (not outsourced), developers that are fluent in the same spoken language, a location and culture that highly values long-term hands-on developer excellence.

- A Scrum Master must be co-located with their teams.

- Each site must feel like a peer, not a second-class citizen.

- Sites must be visited regularly and cross-pollinated.

- In meetings, strive for face-to-face with video tools.

- The use of shared-document tools make it easy for everyone to modify artifacts together and at the same time.

Onwards

Rather than asking, “How can we do agile at scale in our complex and awkward organization?”, ask a different and deeper question, “How can we simplify the organization, and be agile rather than do agile?” And since truly scaling Scrum starts with changing the organization rather than changing Scrum, the next major section focuses on understanding and adopting a simpler customer-focused LeSS organization.

This is followed by major sections on a more customer-focused product and Sprint in a simpler LeSS organization.